Feature Story

Challenge the stigma, pursue your right to health

20 January 2021

20 January 2021 20 January 2021Adolescent girls and young women must boldly and unapologetically seek sexual and reproductive health and rights information and services. The stigma and harmful gender norms associated with sexual and reproductive health and rights are not going anywhere, says Nyasha Phanisa Sithole, a Zimbabwean sexual and reproductive health and rights leader.

“If you are afraid of stigma, then you will not be able to access these services because we are not going to have a stigma-free environment any time soon,” she says.

Working as a sexual and reproductive health and rights advocate and a regional lead for young women’s advocacy, leadership and training at the Athena Network, Ms Sithole believes everyone has a role to play in changing the status quo and influencing decision-making.

“My story is common. It is that of a 16-year-old adolescent girl who needed access to HIV prevention commodities, but only had condoms available and, in rare cases, pre-exposure prophylaxis,” Ms Sithole says, reflecting on her experience as an adolescent.

Despite this common story, the need for comprehensive HIV, sexual and reproductive health and rights and sexual and gender-based violence services in the eastern and southern African region is critical.

Adolescent girls and young women aged 15–24 years account for 29% of new HIV infections among adults aged 15 years and older in the eastern and southern African region, when they only comprise 10% of the population. This means that there are 3600 new HIV infections per week among adolescent girls and young women in the region, which is more than double that of their male peers (1700 weekly).

The stigma and discrimination that young people face, particularly adolescent girls and young women, to access sexual and reproductive health and rights services creates barriers at various levels, including the individual, interpersonal, community and societal levels.

Furthermore, documented health rights abuses include the unauthorized disclosure of health status, being denied sexual and reproductive health and rights services and related psychological violence.

In 2014, Ms Sithole went undercover as a secret client at a youth-friendly health centre in Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital city, in a district with residential areas and schools. The first person she encountered at the centre was a nosy security guard.

“He asked me: ‘What do you need?’ A health screening, I replied. Then he asked, “Asi wakarumwa?” Meaning, “Have you been bitten?” In Shona, this is street language for someone who has a sexually transmitted infection,” she recalls.

Had she not been well-informed, Ms Sithole says she would have felt scared. “It’s something that can scare you or put you off to say, “It’s just a security guard, why are they mocking me or my situation?” Because imagine if I really had a condition that I wanted to manage, what would happen then?”

Ms Sithole said health-care workers sometimes look at adolescent girls and young women accessing sexual and reproductive health and rights services with disdain and judgement and ask, “How old are you and what do you need the condom or contraception for?”

Considering the stigma attached to accessing sexual and reproductive health and rights services, community organizations play a critical role for adolescent girls and young women. Organizations empower them with sexual and reproductive health and rights information and service referrals.

However, COVID-19 greatly impacted how these organizations work in Zimbabwe, which enforced lockdown restrictions to curb the spread of the virus.

“I think all governments weren’t fair when they clamped down restrictions on each and every organization that was working in communities,” Ms Sithole says, adding that it negatively impacted young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health and rights services.

To mitigate these risks, the Global HIV Prevention Coalition, co-convened by UNAIDS and the United Nations Population Fund, came on board to provide financial and technical support to the Athena Network in 10 countries, including Zimbabwe, to establish What Girls Want focal people in each country. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the focal people, who are adolescent girls and young women, mobilized their peers to conduct dialogues via WhatsApp to discuss the issues they face and seek peer support.

Ms Sithole says governments should invest in policy change and development to create an enabling environment where adolescent girls and young women can access sexual and reproductive health and rights and HIV information and services.

Despite the stigma and discrimination attached to seeking sexual and reproductive health and rights services, Ms Sithole says adolescent girls and young women should realize their power and use their agency to get what they need.

“Think about your life because your life is more important than anything else. So, no matter what happens, if you know there is a service you can access, go for it,” she advises.

Region/country

Related

Documents

COVID-19 vaccines and HIV

01 June 2021

English edition updated June 2021. The COVID-19 vaccines authorized by regulators significantly reduce the risk of severe disease and death and are believed to be safe for most people, including people living with HIV. This document is also available in Arabic and Portuguese.

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

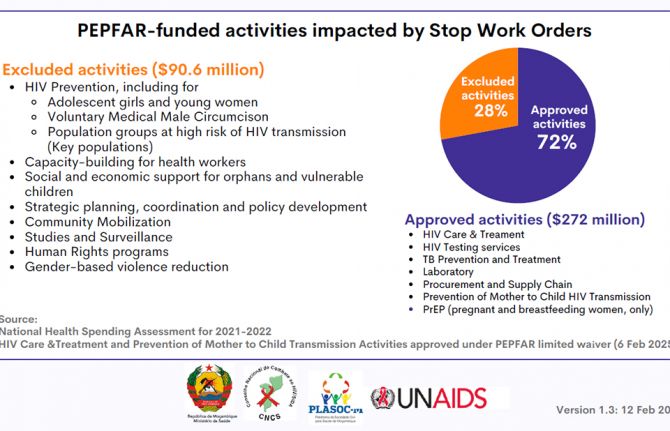

How the shift in US funding is threatening both the lives of people affected by HIV and the community groups supporting them

How the shift in US funding is threatening both the lives of people affected by HIV and the community groups supporting them

18 February 2025

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

Lost and link: Indonesian initiative to find people living with HIV who stopped their treatment

Lost and link: Indonesian initiative to find people living with HIV who stopped their treatment

21 January 2025

Feature Story

Coming together to address the cost of inequality

15 December 2020

15 December 2020 15 December 2020“My business suffered because of corona. Before corona, I would sell at least 10 egg trays a week. At the height of the pandemic, I was lucky if I could sell two trays,” lamented George Richard Mbogo, who is living with HIV, a father of two, and owns a chicken, egg and chips business in Temeke, a district in the southern part of Dar es Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania.

The COVID-19 crisis has adversely impacted the livelihoods of people living with HIV in the United Republic of Tanzania, exacerbating the challenges they face. These include HIV service delivery and widening social and economic inequalities.

“Corona has been a very difficult time. I lived with a lot of worry and stress. Driving a bodaboda (motorbike taxi) requires going into crowds and working closely with people. It has been difficult not to fall into anxiety and depression, balancing getting my HIV treatment and work. I had moments thinking of stopping taking my meds, but I didn’t,” said Aziz Lai, a motorcycle driver who also lives in Dar es Salaam.

Although the colliding pandemics of HIV and COVID-19 are hitting the poorest and the most vulnerable the hardest, through national resource mobilization the COVID-19 crisis has created an opportunity for partners to mobilize in support of the communities they serve.

The collaborative efforts between the government, development partners, including the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, USAID and UNAIDS, the National Council of People Living with HIV (NACOPHA) and community activists have been key in responding to COVID-19, providing information, services, social protection and hope to people living with HIV during these unprecedented and trying times.

One such initiative is Hebu Tuyajenge, run by NACOPHA and funded by USAID, which focuses on increasing the utilization of HIV testing, treatment and family planning services among adolescents and people living with HIV, strengthening the capacity of community organizations and structures and improving the enabling environment for the HIV response through empowering people living with HIV.

Caroline Damiani is a single mother of three who is living with HIV and keeps chicken and ducks for a living. “Hebu Tuyajenge gave us personal protective equipment, sanitizers, soap and buckets and education about COVID-19 and how to take care of ourselves in order to stay healthy during the pandemic,” she said.

Through community-based services that supplement facility-based care, people living with HIV have been linked to and kept on treatment during the crisis by critical peer-to-peer HIV services.

For Elizabeth Vicent Sangu, who has been living with HIV for 26 years, her “numbers” speak for themselves.

“From my community follow-ups, I have returned 80 people to the clinic for CD4 count testing, inspired 240 people to get tests, reported 15 gender-based violence cases and provided education to 33 groups, including youth and church groups,” she said, beaming with pride.

NACOPHA helped Ms Sangu to come to terms with her status and helped her on her own journey of self-empowerment.

“Since becoming a treatment advocate for Hebu Tuyajenge, I have received help with entrepreneurship and education about HIV. I have become a teacher for others. I have made others brave about living with HIV and getting tested,” she said.

The partnership between community advocates and health facilities has paid off.

“Both we and our patients were fearful initially, but due to information and education, things got better. We focused on providing hourly and daily information to patients about corona and made sure that people practised safe social distancing,” said Rose Mwamtobe, a doctor at the Tambukareli Care and Treatment Centre in Temeke.

“Not only in the United Republic of Tanzania, but globally, COVID-19 is showing once again the cost of inequality. Global health, including the AIDS response, is interlinked with human rights, gender equality, social protection and economic growth,” said Leopold Zekeng, UNAIDS Country Director for the United Republic of Tanzania.

“The key to ending AIDS and COVID-19 is for all partners to come together, on a country and global level, to ensure that we leave no one behind,” he said.

Our work

Region/country

Update

New modelling shows COVID-19 should not be a reason for delaying the 2030 deadline for ending AIDS as a public health threat

14 December 2020

14 December 2020 14 December 2020Data reported to UNAIDS by countries have been used to project the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the global HIV response over the next five years. Several scenarios with different durations of service disruptions of between three months and two years were modelled.

The disruptions included: (a) a rate of increase in HIV treatment half the pre-COVID-19 rate; (b) no voluntary medical male circumcision; (c) 20% complete disruption of services to prevent vertical transmission; and (d) no pre-exposure prophylaxis scale-up. An important assumption across all the scenarios was that the current research pipeline would generate one or more safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines, and that the world will succeed in rolling out vaccines globally.

Results from the model showed that COVID-19-related disruptions may result in 123 000 to 293 000 additional HIV infections and 69 000 to 148 000 additional AIDS-related deaths globally. More positively, however, these projections show that the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on the HIV response would be relatively short-lived. Using these projections, UNAIDS and its partners have concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic should not be a reason for delaying the 2030 deadline for ending AIDS as a public health threat.

Our work

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Press Statement

UNAIDS calls for rights-based and people-centred universal health coverage

12 December 2020 12 December 2020GENEVA, 12 December 2020—The world is only 10 years away from the deadline for the universal health coverage target of the Sustainable Development Goals. Only 10 years away from when everyone should have access to quality essential health services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines. But that target seems as far away as ever. In 2017, less than half of the world’s people were covered by essential health services, and if current trends continue it is estimated that only 60% of the global population will enjoy universal health coverage by 2030.

On Universal Health Coverage Day, UNAIDS is calling for the world to meet its obligation— universal health coverage, based on human rights and with people at the centre.

“Health for all: protect everyone” is the theme for this year’s Universal Health Coverage Day, making it clear that health is a fundamental human right.

“It’s a disgrace that inequalities are still impacting the ability of people to access health care,” said Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director. “Health is a human right, but it is so often denied, especially to the most vulnerable, the marginalized and the criminalized.”

Someone’s socioeconomic status, gender, age, sexual orientation, citizenship or race can affect their ability to access health services. Like the HIV response, equality lies at the heart of universal health coverage and progressing towards universal health coverage means progressing towards equity, social inclusion and cohesion. A rights-based and people-centred approach to universal health coverage can help to ensure equitable health for all.

COVID-19 has shown that public health systems have been neglected in many countries around the world. In order to promote health and well-being, countries need to invest in the core functions of health systems, including public health, as common goods for health.

“Money should never determine someone’s access to health,” added Ms Byanyima. “No one should be pushed into poverty by paying for health services. User fees must be abolished and health for all paid for from public funds.”

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the global AIDS response was off track, in part because of a long-term underinvestment in health systems. Universal health coverage and the end of AIDS cannot be achieved and sustained without resilient and functioning health systems that can respond to the needs of everyone, without stigma and discrimination.

The HIV response has shown that communities make the difference. During the COVID-19 pandemic, community-led organizations, including communities of people living with HIV, around the world have mobilized to protect the vulnerable, working with governments to keep essential services going.

Communities have campaigned for multimonth dispensing of HIV treatment, organized home deliveries of medicines and provided financial assistance, food and shelter to at-risk groups. Communities are part of systems for health and are fundamental to attaining universal health coverage. They must be better recognized and supported for their leadership, their innovation and their immense contribution towards health for all.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Contact

UNAIDS GenevaSophie Barton-Knott

tel. +41 79 514 68 96

bartonknotts@unaids.org

UNAIDS Media

tel. +41 22 791 4237

communications@unaids.org

Our work

Press centre

Download the printable version (PDF)

Documents

Executive summary — 2020 Global AIDS Update — Seizing the moment — Tackling entrenched inequalities to end epidemics

07 July 2020

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

Opinion

We must have a #PeoplesVaccine, not a profit vaccine

09 December 2020

09 December 2020 09 December 2020By Winnie Byanyima, UNAIDS Executive Director

The first shots of the COVID-19 vaccine are being administered in the UK this week-a triumph for the British people and a remarkable achievement for all those involved. This historical event, celebrated, quite rightly with much relief and fanfare, shows just what can be done when investment and political will combine to overcome a public health threat. These efforts will undoubtedly save thousands, if not millions of lives.

Yet we are far from claiming victory. New statistics released today by the People’s Vaccine Alliance show that 9 out of 10 people in poor countries are set to miss out on COVID-19 vaccine next year. Once again poorer countries find themselves at the back of the queue and will have to watch many more of their people die before a vaccine becomes affordable for them.

This tragically echoes the early days of the AIDS response when treatment was only available to the rich while poorer countries had to wait years before they could offer their people the same life-saving medicine. This was an avoidable tragedy and we cannot let this happen with the COVID-19 vaccine.

Rich countries have acquired enough doses to vaccinate their entire populations nearly three times over next year. Indeed, rich nations representing just 14% of the world’s population have bought up 53% of all the most promising vaccines so far.

Our best chance of staying safe from COVID-19 is to have vaccines, diagnostics and treatments that are available for all. No-one is safe from COVID-19 until everyone is safe. The response to COVID-19 is reinforcing existing inequalities within and between countries and the global economy will continue to suffer so long as much of the world does not have access to a vaccine.

The current system enables pharmaceutical corporations use government funding for research but maintain monopoly on medicines keeping their technology secret to boost profits. As we learnt from the HIV crisis, this monopoly costs many lives. If history has taught us anything, it is that pharmaceutical corporations create and protect monopolies to maximise profits as a goal higher than improving public health.

Things are moving fast on the vaccine front, yet efforts to improve access to a vaccine are moving far too slowly. The Pfizer /BioNTech vaccine we have seen has already received approval in the UK and it is likely to receive approval from other countries, including the US and EU, within days. Two further potential vaccines, from Moderna and Oxford (in partnership with AstraZeneca) are expected to submit or are awaiting regulatory approval. The Russian and Chinese vaccines have announced positive trial results. Yet all of Moderna’s doses and 96% of Pfizer/BioNTech’s have been acquired by rich countries.

In welcome contrast Oxford/AstraZeneca has pledged to provide 64% of their doses to people in developing countries. However, despite their actions to scale up supply, they can still only reach 18% of the world’s population next year at most.

We must have a #PeoplesVaccine, not a profit vaccine. Unless urgent action is taken by governments and the pharmaceutical industry to make sure enough doses are produced, COVID will continue lay existing inequalities bare. Pharmaceutical corporations and research institutions working on Covid19 vaccines must share the science, technological know-how, and intellectual property related to the vaccines to maximise production by other quality producers. This will allow that enough safe and effective doses to be supplies to all who need the vaccines at the same time. And there is already a global mechanism that facilitates this sharing: the World Health Organization COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP).

I remember the days of the creation of the Medicine Patent Pool for HIV medicines which resulted in production of millions of doses of affordable antiretrovirals that are currently used by people in developing countries. Therefore, we have an example to learn from and make C-TAP works for the millions awaiting a vaccine.

Governments must do everything in their power to ensure COVID-19 vaccines are made a global public good—free of charge to the public, fairly distributed and based on need not ability to pay. A first step would be to support South Africa and India’s proposal to the World Trade Organisation Council this week to waive intellectual property rights for COVID-19 vaccines, tests and treatments until everyone is protected.

The campaign for a #PeoplesVaccine is gaining momentum. Last week in the US, more than 100 high-level leaders from public health, faith-based, racial justice, and labour organizations, joined former members of Congress, economists and artists to sign a public letter calling on President-elect Biden to support a People’s Vaccine. In the EU, a broad coalition of health worker trade unions, NGOs, activist groups, students associations and health experts launched a European Citizens’ Initiative for a people’s vaccine.

Now is time for pharmaceutical companies and governments to step up and ensure that a COVID-19 vaccine is available to everyone, everywhere, free at the point of use. Only then will the world begin to turn the tide on the COVID-19 crisis and ensure that everyone can stay safe and prosper.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Our work

Video

Feature Story

Snapshots on how UNAIDS is supporting the HIV response during COVID-19

03 December 2020

03 December 2020 03 December 2020From the very beginning of the pandemic, UNAIDS has been helping people living with and affected by HIV to withstand the impacts of COVID-19.

In January and February, when COVID-19 forced a lockdown in Wuhan, China, the UNAIDS China Country Office started to receive messages on social media from people living with HIV, expressing their frustration and seeking help.

A survey of people living with HIV in China devised and jointly launched by UNAIDS found in February that the COVID-19 outbreak was having a major impact on the lives of people living with HIV in the country, with nearly a third of people living with HIV reporting that, because of the lockdowns and restrictions on movement in some places in China, they were at risk of running out of their HIV treatment in the coming days.

The lockdowns had also resulted in people living with HIV who had travelled away from their home towns not being able to get back to where they live and access HIV services, including treatment, from their usual health-care providers.

The UNAIDS China Country Office worked with the BaiHuaLin alliance and other community partners to urgently reach the people at risk of running out of their medicines to ensure that they got their medicine refills. By the end of March, special pick-ups and mail deliveries of HIV medicines arranged by UNAIDS had reached more than 6000 people in Wuhan. UNAIDS also donated personal protective equipment to civil society organizations serving people living with HIV, hospitals and others to help in the very early stages of the outbreak.

But the UNAIDS China Country Office didn’t just help people in China. Liu Jie, the Community Mobilization Officer in the UNAIDS Country Office in China, was surprised when she had a call from Poland in March. “A Chinese man introduced himself, saying he is stranded and will run out of HIV medicine in two days,” she said.

With travel restrictions closing down more and more countries, the man could neither return home nor access medicine. Not knowing what to do, he reached out to a Chinese community-based organization and through it contacted UNAIDS in Beijing. A series of phone calls later and the National AIDS Center in Poland followed up—24 hours later, Ms Liu received a photo of the same man who called her, holding up a box of HIV medicine.

The man stuck in Poland wasn’t the only example of UNAIDS helping individuals to get the treatment they needed. By May, UNAIDS had helped hundreds of stranded people to obtain HIV medicine in countries around the world.

A day before Deepak Sing (not his real name) planned to return to India, all international travel ground to a halt, and he was stuck in Luanda, Angola. “I visited more than 10 pharmacies and explored options of delivery of antiretroviral medicines from India to Angola, but without success,” he said. The UNAIDS Country Director for Angola guided Mr Sing towards the national AIDS institute in Angola, which organized a conference call with a medical doctor because one of the medicines that Mr Sing took is not yet in use in the country. The doctor proposed a substitute and in less than 24 hours he picked up his medication.

It was realized early on in the COVID-19 pandemic that one way of ensuring that people on HIV treatment can continue to access their medicines, and to avoid the risk of transmission of the new coronavirus, was to ensure that people living with HIV got multimonth supplies of their treatment.

An early adopter of multimonth dispensing was Thailand, which announced in late March that it would dipense antiretroviral therapy in three- to six-month doses to the beneficiaries of the Social Security Insurance Scheme. After the decision, UNAIDS worked closely with the Ministry of Public Health and partners to advocate for the adaptation of the same policy for all health insurance schemes.

UNAIDS has supported countries worldwide to ensure that people living with HIV access multiple-month supplies of HIV treatment. For example, in Senegal in May, weaknesses in the supply chain, including inadequate assessments of the needs at some clinics for supplies of antiretroviral therapy and irregular supplies centrally, meant that not all people who needed such supplies got them. UNAIDS supported the government in tracking orders of antiretroviral medicines and in strengthening the supply chain.

A modelling group convened by the World Health Organization and UNAIDS estimated in May that if efforts were not made to mitigate and overcome interruptions in health services and supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic, a six-month disruption of antiretroviral therapy could lead to more than 500 000 extra deaths from AIDS-related illnesses and that gains made in preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV could be reversed, with new HIV infections among children up by as much as 162%.

The physical distancing and hygiene recommendations to counter the new coronavirus are particularly difficult for some communities to follow. In April, the UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Eastern and Southern Africa and Reckitt Benckiser joined forces to distribute more than 195 000 hygiene packs to people living with HIV in the eastern and southern African region. Each pack consisted of a three-month supply of Dettol soap and Jik surface cleaner and was distributed in 19 countries through UNAIDS country offices and networks of people living with HIV as part of efforts to reduce exposure to the impact of COVID-19 among people living with HIV.

Kyrgyzstan saw a state of emergency imposed on some regions in March, which resulted in a loss of earnings for many people. The UNAIDS Country Office in Kyrgyzstan, with the support of a Russian technical assistance programme, organized the delivery of food packages for the families of people living with HIV, along with colouring books, marker pens and watercolour sets for the children of people living with HIV, to help them get through the lockdown. “We hope that this small help will go some way to enabling people living with HIV to remain on treatment,” said the UNAIDS Country Manager for Kyrgyzstan at the time.

The UNAIDS Country Office for Angola leveraged its partnerships to reach thousands of people in Luanda with food baskets. UNAIDS and partners provided support to women who inject drugs in camps and settlements in Dar es Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania, while a partnership that included UNAIDS provided cash transfer to vulnerable households in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, for nutrition and food security and basic health kits.

Members of key populations and people living with HIV have been particularly impacted by the response to COVID-19. UNAIDS has supported the rights of gay men and other men who have sex with men, transgender people, sex workers, people who inject drugs and prisoners throughout the pandemic.

The Global Network of Sex Work Projects and UNAIDS in April called on countries to take immediate, critical action to protect the health and rights of sex workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. UNAIDS embarked on a project with the Caribbean Sex Work Coalition to help national networks address sex workers’ knowledge, HIV prevention and social support needs during COVID-19. “Sex workers need to be included in national social protection schemes and many of them need emergency financial support,” said the Director of the UNAIDS Caribbean Sub-Regional Office.

UNAIDS Jamaica provided financial support to ensure that Transwave, a transgender rights organization, had personal protective equipment and to supplement care package supplies and ensured that transgender issues are included in the coordinated HIV civil society response to COVID-19 in the country. “COVID-19 has laid bare just how vulnerable people are when they do not have equitable access to opportunities, justice and health care,” said UNAIDS Jamaica’s Community Mobilization Adviser. “That’s why it’s so important and inspiring that Transwave has continued its core work through all this.”

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, UNAIDS has repeated the call that governments must protect human rights and prevent and address gender-based violence. In June, UNAIDS published a report highlighting six critical actions to put gender equality at the centre of COVID-19 responses, showing how governments can confront the gendered and discriminatory impacts of COVID-19.

“Just as HIV has held up a mirror to inequalities and injustices, the COVID-19 pandemic has put a spotlight on the discrimination that women and girls battle against every day of their lives,” said Winnie Byanyima, the Executive Director of UNAIDS, on the launch of the report.

In August, UNAIDS urged governments to protect the most vulnerable, particularly key populations at higher risk of HIV, in a report intended to help governments to take positive steps to respond to human rights concerns in the evolving context of COVID-19.

In the next month, UNAIDS issued a report that shows how countries grappling with COVID-19 are using the experience and infrastructure from the AIDS response to ensure a more robust response to both pandemics.

In October, UNAIDS issued guidance on reducing stigma and discrimination during COVID-19 responses. Drawing on 40 years of experience from the AIDS response, the guidance was based on the latest evidence on what works to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination and applies it to COVID-19. As with the HIV epidemic, stigma and discrimination can significantly undermine responses to COVID-19. People who have internalized stigma or anticipate stigmatizing attitudes are more likely to avoid health-care services and are less likely to get tested or admit to symptoms, ultimately sending the pandemic underground.

Looking to the future, UNAIDS joined the call for a COVID-19 People’s Vaccine—a vaccine that is affordable and available to all.

Our work

Related

Feature Story

The shero of Butha-Buthe: Matšeliso Setoko

11 December 2020

11 December 2020 11 December 2020Matšeliso Setoko stands at the gates of Seboche Mission Hospital in Lesotho and points at the high mountain peaks in the distance.

“Some of our patients come from beyond those mountains,” she says. “Some of them will walk for two hours before they find a taxi, then will ride in the taxi for another three hours before they get here. Some come on horseback.”

Seboche Hospital is located in Butha-Buthe, Lesotho’s northernmost district, in the village of Ha Seboche, accessible only via a winding dirt road with steep twists and turns. Despite its remote location, the hospital has gained a reputation as a centre of excellence since its founding in 1962 and people are willing to travel long distances to go there.

Ms Setoko is the head of the hospital’s antiretroviral therapy clinic and frequently goes out of her way to ensure that her patients have access to their medicines and adhere to their treatment. Lesotho has the second highest HIV prevalence in the world, with an estimated 340 000 people living with HIV. Twelve thousand are children between the ages of 0 and 14 years.

“We often encounter difficult cases,” she explains. “For example, some children have lost their parents, are diagnosed HIV-positive and are chased out of their relatives’ homes when their relatives find out about the diagnosis. In those cases, I go and talk to the relatives to try and understand why they would do such a thing. I find out who the child’s new treatment supporter is and I work closely with him or her to make sure that the child continues to take their medication.”

The arrival of COVID-19 in Lesotho, however, brought a set of challenges unlike anything that Ms Setoko has faced in her 23 years of working at Seboche Hospital.

In the first week of July 2020, a staff member tested positive for COVID-19 and the hospital was forced to shut down for a week. This coincided with the beginning of a nationwide strike by health workers, who demanded that the government provide them with a COVID-19 risk allowance and adequate personal protective equipment. The strike only ended on 27 July.

“Our services were suspended for most of July, but I knew that I had to find a way to help my patients, particularly the children I work with,” says Ms Setoko. “I’m responsible for about 130 children who are on HIV treatment. So, I went to the filing cabinets and took out all their files and found out that many of them needed refills. I went to the pharmacy and got the medication for all of them—enough for three months.”

Ms Setoko then liaised with her colleagues—lay counsellors, nurses and other staff members—to find out who lived in the same villages as her patients. She assembled packages of medicines for each village and asked her colleagues to take them home. She then called all the children’s carers to inform them that their medicine could be picked up from the hospital staff member living in their village.

Due to COVID-19 travel restrictions, the borders between Lesotho and South Africa were closed from the end of March to the beginning of October. Many of Ms Setoko’s adult patients are migrant workers in South Africa. Before the onset of COVID-19, her patients would regularly travel from South Africa back to Seboche Hospital to collect their three months’ worth of HIV treatment or would send a relative to pick up their medicine on their behalf. With borders closed, however, many found themselves stuck in South Africa for six months. Again, Ms Setoko had to devise innovative solutions to ensure that her patients did not default on their treatment.

“I think I helped around 50 patients who were in South Africa,” she recalls. “If they were about to run out of antiretroviral therapy, I asked them to identify the clinic closest to them and wrote a referral letter for them. I then took a picture of the letter and sent it to them via WhatsApp or else emailed a PDF copy of the letter to the clinic if that was required. I would also call the nurses at the relevant clinic in South Africa to make sure that my patients received the correct antiretroviral medicines.”

There is a low rate of testing for COVID-19 in Lesotho, with less than 2% of the country’s population having been tested.

“The numbers we are seeing do not give us a true picture of what is happening with COVID-19 in this country,” sighs Ms Setoko. “We are not doing enough testing and it can take weeks for people to get their results. We are also not doing enough contact tracing, so it makes it difficult to contain the spread of the virus.”

In the face of such challenges, Ms Setoko recognizes the value of cooperation and solidarity, both at the community and organizational levels, in efforts to continue with HIV prevention and treatment programmes in the era of COVID-19.

“As Seboche Hospital we are lucky to have the support of other organizations, such as our strong partnership with SolidarMed, a Swiss non-profit organization. We also work closely together as staff from different departments, because when people work together, they can achieve any goal.”

Our work

Region/country

Related

Feature Story

The COVID-19 pandemic and women living with HIV: Caroline Damiani

14 December 2020

14 December 2020 14 December 2020Unlike many other countries in the region and the world, no lockdown measures were put in place at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Republic of Tanzania. In June, all restrictions on movement and gatherings were lifted. Nevertheless, the restrictions impacted people’s health and livelihoods, especially those who work in the informal sector, most of whom are women.

Women such as Caroline Damiani, from Chamazi, an administrative ward in the Temeke district of Dar es Salaam.

While, according to the government, about 83% of the 1.7 million people living with HIV in the United Republic of Tanzania are on HIV treatment, this leaves around 300 000 people living with HIV vulnerable. It has been shown that people with underlying health conditions are more susceptible to severe COVID-19 disease.

Thus, COVID-19 is a particular concern for people living with HIV, for both people who are not on HIV treatment and those who are, in ensuring they have access to medicines and health facilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic throws into sharp relief existing inequalities, including gender inequality and economic inequality.

In Chamazi, many women make a living selling homemade food, such as buns, fish or ice cream, or selling groceries in small kiosks.

Ms Damiani, a single mother of three, says her business was greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. “Many people no longer wanted to buy my buns or home-made ice cream. I also couldn’t go to the main market to sell because of the crowds and the risk it brought. I then decided to switch completely to selling groceries at a small kiosk and rearing ducks and chickens to sell,” says Ms Damiani.

Ms Damiani has been living with HIV since 1998. All her three children are HIV-negative. Her husband divorced her and married another woman due to her HIV status and pressure from his family. To date, she still does not know his status. She lives with her daughter and granddaughter as her sons each have their own families. Her daily routine now includes feeding her ducks and chickens, helping her granddaughter with her schoolwork, performing household chores and tending her kiosk.

Ms Damiani says the COVID-19 pandemic affected her mental health. “I don’t have many friends and I spend most of my time at home or at the church. My stress levels increased in the earlier days of the pandemic and I began to lose weight,” she says.

“Fortunately, I never stopped taking my HIV treatment due to the insistence of my doctors that I adhere to my treatment regimen,” she says. “I am now determined to show everyone that you can live a full and healthy life as long as you don’t stop taking your medication.”

“The education and support we received from the Hebu Tuyajenge project also greatly helped to alleviate my stress.”

Hebu Tuyajenge is an initiative of the National Council of People Living with HIV, with support from UNAIDS and funded through USAID.

It focuses on increasing the utilization of HIV testing, treatment and family planning services among adolescents and people living with HIV, strengthening the capacity of community organizations and structures and empowering people living with HIV. In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic its members educated people living HIV on how to protect themselves from COVID-19.

“In my community, one of the biggest problems was the lack of education and information surrounding COVID-19. Most of us didn’t even know how to properly wash our hands to reduce the risk of catching the virus,” says Ms Damiani.

The Hebu Tuyajenge project is an example of how the government, development partners, civil society and community activists have been key in responding to COVID-19 in the United Republic of Tanzania, providing information, services, social protection and hope to people living with HIV during these unprecedented and trying times.

“The efforts by the government and other donors should continue. Things have now improved in the country because everyone is now aware of the pandemic and people continue to take precautions,” says Ms Damiani.