Feature Story

A united rallying cry: Time to make health care systems more flexible and innovative

16 April 2018

16 April 2018 16 April 2018Seven months after launching the catch-up plan in western and central Africa, progress on increasing the numbers of people on antiretroviral treatment continues to lag in the region. Many countries will not reach key targets by 2020 if the current systems remain unchanged.

"Overall we saw a 10% percent increase of people on treatment, which is not enough," said UNAIDS Executive Director Michel Sidibé. "Now, there is even more a sense of urgency."

Mr Sidibé, however, pointed to the success in the Democratic Republic of Congo where there was a clear increase in the number of people living with HIV accessing ARVs. The reasons for the positive trend included civil society and political leadership working closely together as well as community HIV testing and the training of 11 000 health care workers.

"More than ever there is a need to rethink health systems and alternatives for people to access health care," he said.

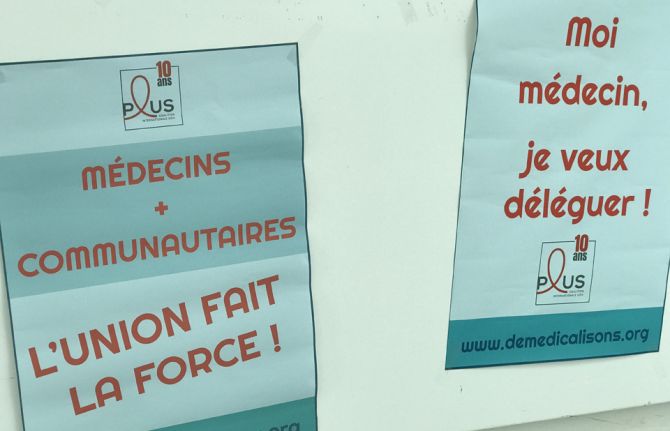

The call to delegate patient care to communities was a major rallying call during AFRAVIH, the international francophone HIV and hepatitis conference held in Bordeaux, France, early April. Mr Sidibé briefly shared the stage at the opening ceremony with the civil society organisation Coalition PLUS. They declared that the key to success in ending AIDS involved joining forces between doctors and community health workers and giving more leeway to communities to respond to the local needs of their own people.

Under the banner, "De-medicalize" the organisation explained that doctors will never be replaced but that there were too few of them and people living with HIV didn't require acute care.

Coalition Plus' recent report states that governments and the medical practitioners should delegate more tasks to nurses and community health workers. In addition to allowing for more targeted prevention and faster access to treatment, delegation of non-medical tasks would lighten the load on overburdened health systems. West and central Africa represent 17% of the total population living with HIV but 30% of deaths in the region are from AIDS-related illnesses. This is a region, according to UNAIDS and its partners, that can truly benefit from community models of care.

What worries Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is the risk of a significant drop in resources for treatment will hamper recent improvements in west and central Africa. This concern stems from the fact that Global Fund estimates a 30% drop in fund allocations to the region for 2018 – 2020 compared to signed HIV grants in the previous allocation period. In 2016, MSF was among the first to sound alarm bells regarding the region's high HIV death toll and the up to 80% of children unable to access antiretroviral therapy. MSF HIV Policy Advisor and Advocacy Officer Nathalie Cartier said that they supported the west and central Africa catch-up plan but that it needed to be fully implemented. "Political will has been promising but now it's time to make it a reality on the ground so that people living with HIV can reap the benefits," she said.

Global Fund supported the catch-up plan and works closely with countries in order to maximize the impact of the investments. They believe that leveraging additional domestic financing for health is crucial to increase country ownership and build sustainable programs.

All the more reason to decentralize healthcare systems and capitalize on innovations to keep health costs down. HIV self-testing, new medicines and high impact strategies involving communities are critical to improving efficiencies. "With point-of-care (POC) testing in communities and homes, delays are minimal between diagnosis and initiating treatment," said Cheick Tidiane Tall, Director of Réseau EVA, a network of pediatric doctors specialized in HIV care. “In the long run, that's a lot of people and resources saved,” he added.

Côte d'Ivoire Infectious and Tropical Diseases professor Serge Eholié couldn't agree more. "Flexible health care systems capitalizing on various innovations makes a lot of sense," he said. Turning to the Minister of Health in the Central African Republic, Pierre Somse, he asked, 'How do you respond?'

Mr Somse, also a trained doctor, said, "We doctors will stay doctors. However, there is a need for us to lean on communities and vice versa." He added, "at the heart of the issue are patients and they are and should always be the priority."