UNAIDS in action

Related

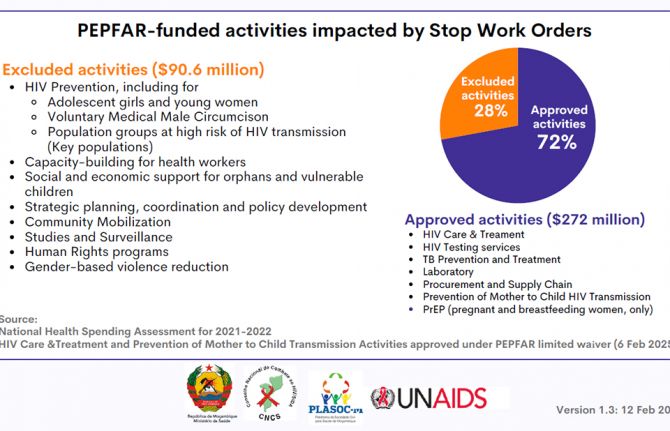

How the shift in US funding is threatening both the lives of people affected by HIV and the community groups supporting them

How the shift in US funding is threatening both the lives of people affected by HIV and the community groups supporting them

18 February 2025

UNAIDS urges that all essential HIV services must continue while U.S. pauses its funding for foreign aid

UNAIDS urges that all essential HIV services must continue while U.S. pauses its funding for foreign aid

01 February 2025

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

Documents

UNAIDS Gender Action Plan 2018–2023 — A framework for accountability

05 June 2018

Gender equality in the workplace is a human right and critical to the performance and effectiveness of UNAIDS. Organizations with more equal representation of women at the senior management level considerably outperform their counterparts with a lower representation of women in senior positions. Gender-balanced teams have greater potential for creativity and innovation and contribute to better outcomes in decisionmaking. The centrality of advancing gender equality, including through the achievement of gender parity, is increasingly being recognized, as signalled by the historic System-wide Strategy on Gender Parity, launched by the United Nations Secretary-General in 2017.

Related

UNAIDS calls for rights, equality and empowerment for all women and girls on International Women’s Day

UNAIDS calls for rights, equality and empowerment for all women and girls on International Women’s Day

06 March 2025

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

A shot at ending AIDS — How new long-acting medicines could revolutionize the HIV response

21 January 2025

Press Statement

UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board Bureau releases terms of reference for work of the Independent Expert Panel on harassment

07 May 2018 07 May 2018GENEVA, 7 May 2018—The scope and nature of the work of the Independent Expert Panel on prevention of and response to harassment, including sexual harassment, bullying and abuse of power at the UNAIDS Secretariat has been decided upon by the UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board (PCB) Bureau following consultations with the three constituencies of the PCB. The PCB Bureau is composed of the United Kingdom, China, Algeria, the PCB nongovernmental organization delegation and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, representing the UNAIDS Cosponsors. The agreed terms of reference will guide the panel’s work over the coming months.

Under the terms of reference, the panel will:

- Review the current situation in the UNAIDS Secretariat with regard to harassment, including sexual harassment, bullying and abuse of power and retaliation—including by looking back over the past seven years—to assess the organizational culture at headquarters and the regional and country offices.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of existing policies and procedures to prevent and address harassment, including sexual harassment, bullying, retaliation and abuse of power in the UNAIDS Secretariat workplace.

- Recommend a comprehensive set of prioritized measures on organizational culture, policies and fair and due process procedures with respect to harassment, including sexual harassment, and bullying, retaliation and abuse of power in the workplace.

The panel will review all relevant areas. It will look at UNAIDS’ leadership and culture, policies and strategies to prevent harassment and the reasons for the low levels of formal reporting of harassment. In addition, the panel will review the investigation processes applied by the UNAIDS Secretariat and will make recommendations on how to ensure that these are fit for purpose and fair. The panel will also make recommendations to ensure that the UNAIDS Secretariat has sufficiently strong internal systems to identify unacceptable behaviour and take swift action in response to it and will make recommendations to ensure that accountability is visible and ensured at all levels of UNAIDS.

In its work, the panel will draw from lessons learned and best practices from other United Nations organizations and other partners. The panel is independent of UNAIDS’ senior management and in its work will consult with United Nations Member States, PCB nongovernmental organizations, UNAIDS Cosponsors and former and current UNAIDS staff.

“I fully support the panel’s work and how the UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board has conceptualized the panel as one composed of independent experts. I will provide whatever is needed to ensure that the Board leadership can continue to run a transparent process. I look forward to the panel’s report and pledge to swiftly implement its recommendations,” said Mr Sidibé.

Called for in February 2018 by Mr Sidibé, the panel is one of several measures designed to strengthen the culture of zero tolerance for harassment, abuse and unethical behaviour at UNAIDS. Other measures announced in February include the five-point plan, which aims to ensure that inappropriate behaviour and abuse of authority are identified early on, that measures taken are properly documented and that action to be taken follows due process and is swift and effective. The five-point plan also calls for enhanced protections for plaintiffs and whistle-blowers. The recommendations of the panel are expected to influence the implementation of the five-point plan.

The panel will comprise up to five independent experts. It will deliver its final report with its recommendations to the 43rd meeting of the PCB in December 2018.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Feature Story

Bringing about change

25 April 2018

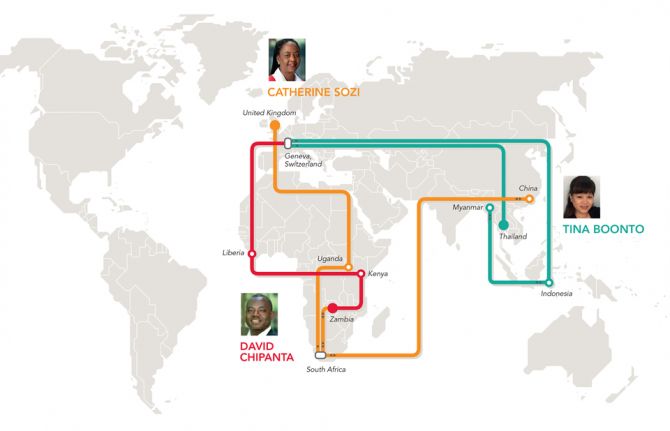

25 April 2018 25 April 2018David Chipanta started his UNAIDS career in Liberia as the UNAIDS Country Director, where he helped to strengthen the national AIDS commission and national strategy framework. He is particularly proud of putting gender and ending sexual violence front and centre in the AIDS response in the country and giving the national network of people living with HIV more of a voice.

“What I found exciting was tackling the many barriers that surround access to HIV treatment, prevention, care and support,” he said. By barriers, he means the stigma, discrimination, poverty and inequalities that constrain people from accessing HIV services.

An economist by training, Mr Chipanta remarked, “We cannot forget the importance of all the things that relate to people’s lives—do they feel secure, do they have food, do they have a house, a family, a job?” Giving the example of Zambia, he described some people only taking their HIV medicine during the rainy season because food is more readily available then.

“It hit me that the peripheral stuff is very important, because without it HIV services will have a limited impact,” Mr Chipanta said. His current job as the UNAIDS Social Protection Senior Adviser in Geneva, Switzerland, focuses on just that—connecting people affected by HIV to social safety nets and improving livelihoods, as well as reducing poverty and improving education.

“UNAIDS has created more awareness about social protection services and the hurdles that people living with HIV face,” he said. For example, he explained that in Liberia and Sierra Leone, sex workers said they weren’t accessing social protection services because the administrators often treated them badly; in response, his office set up sensitivity training.

Another issue close to his heart is girls’ education. Keeping girls in school has been shown to lower HIV prevalence and is an important factor in increasing access to HIV treatment. “In low-income settings, we shone the light on the importance of cash transfers to keep girls in school,” Mr Chipanta said. His next challenge is advocating for more synergies with programmes for mentoring, empowerment and social support.

“As a person living with HIV, I never thought I would accomplish so much,” he said. In 1991, when he found out his HIV status in his native Zambia, he assumed that his life was over. “I thought, before I die, let me help others,” he added.

“I was personally motivated to work in the HIV field,” he said. “But I felt like I wanted to become an expert in my own right.”

Krittayawan (Tina) Boonto reflected on her 20 years at UNAIDS by also saying she couldn’t believe how far she had got. Ms Boonto started work in her native Thailand before moving to Geneva.

“It was supposed to be temporary, but I stayed seven years,” she said.

She then went to Indonesia as the Programme Coordination Adviser in 2005. She helped the Ministry of Health with technical support and accessing financial resources from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. That experience proved pertinent, because in 2010 she moved to Myanmar as the Senior Investment and Efficiency Adviser.

“The country was opening up at that time, so my field experience in other countries came in handy,” she said. For example, UNAIDS advocated to decentralize the provision of antiretroviral medicines so that people from rural areas could get their treatment at primary health-care centres without traveling to the main cities.

“It was so rewarding to be on the ground and witness the change.” According to Ms Boonto, antiretroviral medicine access shot up to more than 120 000 people accessing the medicines, up from 30 000 people in three years.

“That’s when I realized that it’s not just about money, it’s also about the willingness to change,” she said.

A year ago, she returned to Indonesia, but this time as the UNAIDS Country Director. It’s been challenging for her because despite the scale-up when she was in the country the first time, Indonesia lags behind its neighbours, such as Thailand and Myanmar, in terms of antiretroviral medicine access and reducing new HIV infections. “It ranks third after India and China in the region in terms of new HIV infections,” Ms Boonto said.

Her tactic has been to raise HIV awareness among decision-makers and stress to them that the epidemic is not under control. “We present data and push to keep HIV a priority,” she said. Recently, she has been knocking on doors to raise alarm bells about tuberculosis—a disease that remains one of the leading causes of death among people living with HIV, despite being treatable and preventable.

“It all boils down to political will and getting the autonomous country districts on board once the Ministry of Health approves,” she said. Not flinching, Ms Boonto said, “My job never lets me forget what I am working for: people living with HIV.” She added, “We are still relevant and are still much needed, and that is the greatest satisfaction of all.”

Satisfaction for Catherine Sozi has been observing the shift from, “How can we roll out treatment for so many people, to getting 21 million people on treatment in the space of 10 plus years,” she said. In her third stint in South Africa, she feels UNAIDS’ advocacy work has paid off. Recalling a conversation she had in Zambia with the government when she worked there 15 years ago, many feared that the money and support would not come if countries started to offer antiretroviral medicines. “I made the case that money would come based on the countries’ growing commitment and that we would work to get the prices down,” she said. In 2005, prices for antiretroviral medicines were high. “The governments listened to us and to civil society and, based on solid results in 2015, it suddenly looked feasible to put an end to AIDS,” Ms Sozi said.

As the Regional Director for the eastern and southern Africa region, she is thrilled by the positive energy in the region, despite the many challenges remaining. “A lot still needs to be done to stop new HIV infections, get even more people on treatment and have them stay on treatment, and that includes testing even more adolescents, children and adults for HIV, including key populations,” she said. Another big issue involves tackling rampant sexual violence, which leads in part to higher numbers of new HIV infections among girls and young women, she explained.

“In this case, a biomedical response won’t help. We need to change how we relate to households, the police and the legal system and get faith leaders, women activists, nongovernmental organizations and men involved to turn things around,” Ms Sozi said. Trained as a doctor in Uganda, she admits that her career has propelled her into a much wider arena than she had ever anticipated.

“The UNAIDS women’s leadership programme empowered me to become a leader and reassured me that I could manage a large, diverse staff as well as resources and still be technically strong,” she said.

Her four years as the UNAIDS Country Director in China, before her latest move to South Africa, proved to be very enriching on a personal and professional level. “As a family we had a wonderful time in a country that is in itself so diverse in all aspects,” she said. The commitment by the government and civil society to work on the epidemic was both invigorating and challenging.

One of her biggest accomplishments in Asia was her contribution to the China–Africa health dialogue. “For me, to support the South–South dialogue on China–Africa health cooperation meant a lot,” Ms Sozi said. “I see myself as a facilitator of change.”

MORE IN THIS SERIES

UNAIDS staff share global experience on AIDS through criss-crossing the world

It’s about the people we serve: UNAIDS staff connecting the world

More in this series

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Feature Story

It’s about the people we serve: UNAIDS staff connecting the world

29 March 2018

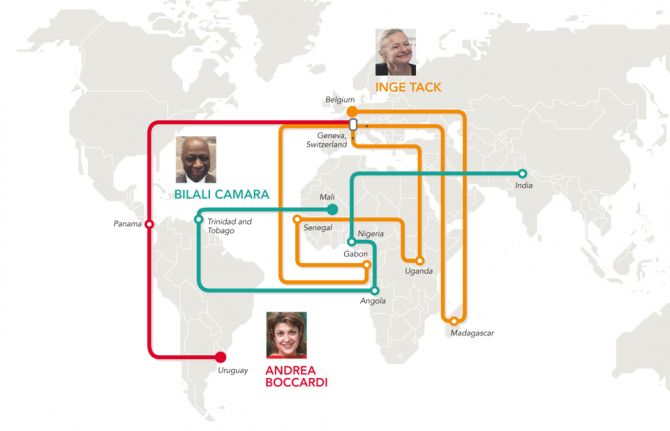

29 March 2018 29 March 2018“Partnerships, partnerships, partnerships,” said Inge Tack. “That’s what motivates me every morning.”

Partnerships are also her background. When she joined UNAIDS in 1999, she worked on a new initiative, the International Partnership against AIDS in Africa, which involved getting buy-in from governments, the private sector, the United Nations and communities. She then moved to Uganda as the Technical Adviser helping the national AIDS commission with its various constituencies. Ms Tack then headed to western Africa, to the UNAIDS regional bureau to become the Partnerships Adviser.

“I travelled to many of the 19 countries in that region, where travelling is not easy, but I loved the job,” she said. “Supporting country offices, being the broker and convener at the regional level for governments, regional economic communities, donors and people living with HIV in a challenging environment was definitely a huge learning experience,” Ms Tack said. Gaining everyone’s trust was key, she added. She also relished the role because UNAIDS’ neutrality and expertise, she explained, made it the go-to office for HIV.

In 2012, Ms Tack became UNAIDS Country Director in Gabon, allowing her to zero in on one country. “I was the boss of a very small team, but with an enormous scope to do it all,” she said. The variety thrilled her.

“I never had a dull day in Gabon,” she said describing a typical day, which could take her to the presidential palace in the morning, an HIV workshop in the afternoon and an evening meeting discussing health with investors.

Aside from partnerships, she forged real connections with people.

“At the end, it is all about people, giving them hope and encouraging them to help each other,” Ms Tack said. A lot of young people have limited opportunities, so she became a sort of cheerleader for them.

In one case, a young mother living with HIV came to her office saying she could no longer bear her life. Ms Tack sensed that the young woman could perhaps share her story with other teens. “It blew me away how she recounted her tale and connected to people,” she said. Slowly but surely, the young woman gained confidence. The Gabon office helped launch a network for young people living with HIV to raise awareness about HIV prevention and to guide people on adhering to treatment. “And you know what?” she asked. “That woman now has become a community health worker, paid for by the local mayor’s office,” she said beaming.

Ms Tack’s new job in the Programme Partnerships and Fundraising Department has brought her back to Geneva, Switzerland, closer to her native Belgium. Fundraising has changed so dramatically that she wanted to come back to headquarters and refresh her skills. “I believe it’s important to match funds to real country needs,” she said. She also thinks that UNAIDS needs to innovate more on raising funds. Looking up from her computer, she said, “When I feel like I have gotten a good handle on that, then I can return to the country level and put it into implementation!”

UNAIDS staff work in 79 country offices and six regional offices and at its headquarters in Geneva. It also has liaison offices at the United Nations Headquarters in New York and in Washington, DC, United States of America, and at the African Union in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The nearly 700 staff members come from 123 countries and more than 60% of the staff work in the field.

Bilali Camara joined UNAIDS in 2008 in Trinidad and Tobago as a Regional Monitoring and Evaluation Adviser. “I had to establish a strong network at national levels across the Caribbean,” he said. This involved a lot of sharing of lessons and problem-solving, he explained. When he moved to Angola as the Country Director, his networks involved fewer people, but he networked tirelessly. He’s particularly proud of having connected a basketball coach with a radio director to air zero discrimination messages. For the next campaign he asked a famous musician, a transgender singer, to help. As a result, he said, they reached thousands of people with HIV awareness messages.

Mr Camara reiterated this endeavour when he became the Country Director in Nigeria. In this instance, he explained, the real push involved lowering the number of babies becoming infected with HIV. Too few pregnant women knew their HIV status and their babies were being missed by HIV services. “We had to reach people, and the best way to do that was contacting them by phone,” Mr Camara said. UNAIDS Nigeria partnered with a telecom company and millions of people received HIV prevention text messages. “With that momentum, HIV testing became part of the prenatal care package in the country,” he said.

Mr Camara said that what keeps him moving forward is people tell him that they appreciate what UNAIDS has done.

Forward and onward he has gone. Mr Camara just became the UNAIDS Country Director in India. What has struck him so far is how involved the key populations are in the AIDS response. “The level of ownership here has truly impressed me,” Mr Camara said. “When it comes to public health, if communities lead the way, then that is a sign of success.”

Success for Andrea Boccardi saw her start out as an obstetrics and gynecology doctor advising Uruguayan Army peacekeeping operations and learning about the HIV policy and programming of the United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations. She now focuses on gender-based violence and the elimination of discrimination.

“It’s a dream come true,” she said. “I now have the opportunity to implement the UNAIDS vision of zero discrimination in health-care settings.” Standing in her office, her walls decorated with certificates and photos of Uruguay, Panama and Geneva, she explained how privileged she has felt to have moved around the world and departments.

In 2003, UNAIDS hired her as an HIV Adviser on Security and the Humanitarian Response in Latin America, ending her career as a military doctor. She recalls that her past job came in useful when she trained United Nations peacekeeping troops deploying to Haiti and the Congo.

Two years later she transferred to Panama. Ms Boccardi helped open the UNAIDS regional office, working on programming and technical support. “I did a lot of running around trying to make sure that we were on top of human rights, prevention, treatment and universal access to health,” she said, sighing at the thought of what that entailed.

When her rotation came up, Ms Boccardi said she wanted to move beyond policy and work towards the UNAIDS global prevention agenda to bring change on the ground. Her transition to headquarters in Geneva was seamless. She described her daughters having a tougher time with the French homework, but overall loving the independence that the vast Swiss bus and train system gives them.

In the past 10 years, nearly 500 staff have participated in mobility and more than 400 staff have been reassigned to multiple duty stations. In 2018, about 30 staff members will move from their current posts to new posts.

After working on prevention, Ms Boccardi recently joined the Human Rights and Gender Team.

Pointing to the Spanish words engraved at the bottom of a framed pre-Columbian small gold frog by her desk that read, “Leader, guide, friend”, Ms Boccardi said this had become her mantra in life to balance work, family and friends.

More in this series: UNAIDS staff share global experience on AIDS through criss-crossing the world

Related

Feature Story

UNAIDS staff share global experience on AIDS through criss-crossing the world

19 March 2018

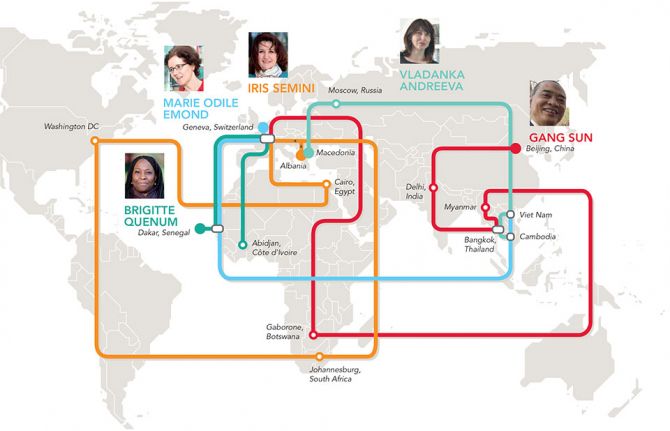

19 March 2018 19 March 2018When Marie-Odile Emond first arrived in Cambodia, she didn’t realize that some of the UNAIDS/International Labour Organization policy on HIV in the workplace she had heard discussed, years back, at the global level would be something she would see implemented.

“It seemed so abstract and yet here I was seeing it in practice,” she said, referring to health and human rights protection for workers, notably sex workers, which involved the Ministry of Labour, the community and the United Nations. “As the Country Director, I facilitated the dialogue and training for that to happen,” Ms Emond said, “and now it serves as an example for other countries.”

She now heads the Viet Nam Country Office, which she said offered another set of challenges and opportunities.

“I have found it really interesting to alternate between global, regional and country offices, because each offers a window to a part of our strategy,” Ms Emond said. Rattling off the many countries she has worked in at UNAIDS, she laughed and said, “Oh, and before UNAIDS, I worked in Armenia, Burundi, Liberia and Rwanda.”

In her opinion, meeting so many committed people from all walks of life and building bridges with them has been enriching. It’s made all the difference, according to her, in the AIDS response. “I play the coordinator, but I also had an active role in making people believe in themselves,” Ms Emond said.

Country Director Vladanka Andreeva said that her moves within UNAIDS were a huge change each time. She has served across two regions in different roles and credits her professional growth to her colleagues and the various communities she has interacted with.

“In every new post there was a challenge to quickly adapt to it, establish relationships with stakeholders and make a contribution,” she said. “You really have to hit the ground running.” Her role as the Treatment and Prevention Adviser in the UNAIDS regional office in Bangkok, Thailand, before going to Cambodia, really stands out for her. Ms Andreeva provided technical advice and assistance to strengthen HIV programmes across the region. This involved facilitating knowledge and sharing best practice, in and between countries, on innovative delivery models to scale up access to evidence-informed services.

She added that, from the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia to Cambodia, “my family and I explored the cultural heritage of our host countries, tasted some of the most delicious pho, tom yum and amok, and made friends from all over the world.”

She thanked her husband and daughter for being fantastic partners in the journey, since moving every four to five years is no small task. UNAIDS staff move routinely from one duty station to another, criss-crossing the world throughout their careers.

Her real pride is seeing her 17-year-old daughter, who was six when they started living abroad, become a truly global citizen, with such respect for diversity.

Gang Sun echoed many of Ms Andreeva’s points. “Because we interact with so many stakeholders, from the private sector to government to civil society, I have learned to always show respect and always listen,” he said.

For him, the journey started in the field in China, India and Thailand, followed by Myanmar and Botswana, before starting his new job at UNAIDS headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, in 2017. He described that adapting to different cultures has kept him on his toes. “Overall, in my career I have seen every challenge as an opportunity and I have gained in confidence,” he said.

What fascinated him the most was the differences between working in high HIV prevalence countries and in countries where the epidemic was concentrated among key populations. In his new role at headquarters, he now taps into his expertise gained along the way as well as that of so many colleagues within UNAIDS and the World Health Organization.

“Despite all my experience, I still have more learning to do,” Mr Sun said.

The Côte d’Ivoire Country Director, Brigitte Quenum, jumped at the opportunity to go to the field after more than five years in Geneva. As the Partnerships Officer with francophone countries at UNAIDS headquarters, she said she learned a lot about how the UNAIDS Joint Programme functioned. That has helped her in her current role working hand in hand with Cosponsors, financial partners and civil society.

Before working in Geneva, she worked in the western and central Africa regional UNAIDS office in Dakar, Senegal. “I have gone full circle, and that has been very rewarding, because I know how the entire organization functions,” Ms Quenum said. Reflecting on the recent change in her life, aside from adjusting to the muggy coastal weather and the sheer population size of Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire—the city has as many people as all of Switzerland—she said, “Being on the ground gives one’s job more of a sense of urgency, but I think it’s because we have daily contact with the multiple communities we’re serving.”

More in this series: It’s about the people we serve: UNAIDS staff connecting the world

Related

Press Statement

UNAIDS welcomes appointment of Natalia Kanem as Executive Director of UNFPA

05 October 2017 05 October 2017GENEVA, 5 October 2017—UNAIDS welcomes the appointment by the United Nations Secretary-General of Natalia Kanem as the Executive Director of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

“As part of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, the United Nations Population Fund’s work is critical in meeting the reproductive health needs of women and adolescents,” said Michel Sidibé, Executive Director of UNAIDS. “I look forward to working closely with Ms Kanem. Her experience in public health, her strong leadership and her commitment to social justice will be invaluable in our efforts to end AIDS as a public health threat.”

UNFPA is the lead United Nations agency for delivering a world where every pregnancy is wanted, every childbirth is safe and every young person's potential is fulfilled. UNFPA’s response to HIV is integral to its goals of achieving universal access to sexual and reproductive health and ending gender-based violence. UNFPA promotes integrated HIV and sexual and reproductive health services for young people, key populations, and women and girls, including people living with HIV.

As part of UNFPA’s work on HIV prevention, Ms Kanem is co-convening a meeting of the Global Prevention Coalition with Mr Sidibé to finalize work on the HIV Prevention 2020 Road Map, a road map to accelerate HIV prevention efforts and reduce new HIV infections by 75% by 2020.

UNFPA is one of UNAIDS’ 11 Cosponsors working to end the AIDS epidemic as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. UNFPA is also part of the H6 partnership, which pulls together the collective strengths and distinct capacities of six United Nations agencies, related organizations and programmes to improve the health and save the lives of women and children around the world.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Press centre

Download the printable version (PDF)

Update

UNAIDS fully compliant with UN-SWAP

22 August 2017

22 August 2017 22 August 2017UNAIDS has been recognized for meeting or exceeding all of the 15 performance indicators of the United Nations System-wide Action Plan on Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN-SWAP), a year ahead of the deadline established by the United Nations System Chief Executives Board for Coordination.

In a letter sent by Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Executive Director of UN Women, to Michel Sidibé, Executive Director of UNAIDS, the organization is commended for its significant dedication to gender equality and women’s empowerment at all levels. UNAIDS has achieved overall gender parity at the professional and higher levels and has created an enabling work environment through extended maternity leave and flexible working conditions.

The findings of UN-SWAP reaffirm UNAIDS’ role as a leader for gender equality and the empowerment of women across the United Nations system. UNAIDS meets or exceeds the requirements of 100% of the UN-SWAP performance indicators, compared to only 64% for the overall United Nations system. In addition, UNAIDS exceeds the requirements for 53% of the indicators, compared to 19% for the overall United Nations system.

Since the inception of UN-SWAP, UNAIDS has demonstrated continued progress in each annual report and has commitment to improving its UN-SWAP scoring in at least one performance indicator over this year.

UN-SWAP is a United Nations system-wide accountability framework designed to measure, monitor and drive progress towards a common set of standards for the achievement of gender equality and the empowerment of women. Sixty-five entities, departments and offices of the United Nations system report on it every year.

Quotes

“Gender equality and women’s empowerment is at the heart of ending AIDS. We are proud to have achieved all UN-SWAP performance indicators and will continue to work to achieve even better results, while sharing our experiences to inspire more and quicker progress across the United Nations system.”

Related

Feature Story

Accurate and credible UNAIDS data on the HIV epidemic: the cornerstone of the AIDS response

10 July 2017

10 July 2017 10 July 2017Once a year, UNAIDS releases its estimates on the state of the worldwide HIV epidemic. Since the data can literally affect life and death decisions on access to services for treatment and prevention—and are used to decide how to spend billions of dollars a year—they need to be as accurate as possible and be regarded as credible by everyone who uses the information.

How we collect and interpret HIV data has huge consequences—a pregnant woman visiting an antenatal clinic can help calculate the size of the country’s HIV epidemic, can help shape national policies for the response to HIV and can influence the size of grants to respond to HIV from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and others.

So, how do we do it?

Collecting data on the ground

We don’t count people. We can’t—many people who are living with HIV don’t know that they are, so can’t be counted. And everyone in a country can’t be tested every year to calculate the number of people living with HIV. Instead, we make estimates.

The data that are published in our reports, quoted in speeches and used by governments around the world to plan and implement their AIDS responses originate on the ground, in a clinic, in a hospital or anywhere else that people living with HIV access, or need, HIV services.

Take the example of a pregnant women visiting an antenatal clinic as part of her routine antenatal care. She will be offered an HIV test, which will show her to be either HIV-positive or HIV-negative. An HIV-positive result will, of course, open up for the individual mother the range of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services available to keep her well and her baby HIV-free, but the result, whether negative or positive, will also be used to determine the wider impact of services and the success of country programmes.

Some countries operate a so-called sentinel survey system, in which a network of reporting sites collect data. If the clinic is one of these, a sample of blood will be anonymized and collected with results from the other sentinel sites, resulting in a large set of data to estimate trends from the sentinel sites over time.

In other countries, data from all women who are being tested routinely at all antenatal care sites are used to estimate HIV prevalence. Her test result will be recorded and passed on to the country’s national-level HIV reporting agency.

Data from antenatal clinics, when combined with information from broader, but less frequently collected, population-based surveys, are the basis for HIV data collection in countries where HIV has spread to the general population.

For countries that have HIV epidemics mainly confined to key populations, data from HIV prevalence studies among those key populations are most often used. These prevalence studies are combined with the estimated number of people in those key populations—an estimate that is difficult to make, given that behaviours of key populations are outlawed in many countries.

In countries in which doctors are required to report cases of HIV, and if those data are reliable, those direct counts are used to estimate the epidemic. An increasing number of countries are setting up systems that use reported cases of HIV diagnoses.

Survey types

Population-based survey: a survey that is conducted in a random selection of households in a country. The survey is designed to be representative of all people in the country.

HIV prevalence study: a study of a specific population that collects blood samples from the population to determine how many people in that population are living with HIV. Typically, the results of that test are provided to the survey respondent.

Number crunching

Once a year, the country’s reporting agency will, helped by UNAIDS and partners, make estimates of the number of people living with HIV, the number of people on HIV treatment, the number of new HIV infections, etc., using software called Spectrum, which uses sophisticated calculations to model the estimates.

For estimates relating to children, a whole range of information, such as fertility rates, age distributions of fertility and the number of women in the country aged 15–49, is taken into account when computing the final numbers.

Estimates for different populations and age groups are calculated by Spectrum, taking into account different types of demographic and other data, building up a comprehensive picture of the country’s HIV epidemic.

The Spectrum estimates are sent to UNAIDS at the same time as the collection of the annual Global AIDS Monitoring reporting on the response to the HIV epidemic in the country. UNAIDS compiles and validates all the Spectrum files and uses the country-level data to make global estimates of the HIV epidemic and response.

UNAIDS publishes estimates for all countries with populations greater than a quarter of a million people. For the few countries of that size that do not develop Spectrum estimates, UNAIDS develops its own data, based on the best available information.

Ranges are important

In 2015, there were 36.7 million [34.0 million–39.8 million] people living with HIV in the world. The numbers in the brackets are ranges—that is, we are confident that the number of people living with HIV is somewhere within the range, but can’t say for sure what the definite number is.

All UNAIDS data have such ranges, but why can’t we be more accurate? UNAIDS data are estimates, which vary in their accuracy, depending on several factors. The size of sample taken for the estimate affects the range—a large sample means a small estimate range, and vice versa; if a population-based survey is conducted in a country, the estimate range will be smaller; and the number of assumptions made for an estimate has an impact on how narrow the range will be.

If it’s found to be wrong, it’s fixed

UNAIDS’ models are regularly updated in response to new information. For example, this year’s data will show a slight rise in the reported number of children becoming infected with HIV. This isn’t a real rise in young children acquiring HIV, but an adjustment in our knowledge of how infections occur in real life—in fact, once we apply this updated knowledge to previous years, we see that the number of new HIV infections among infants was higher then too.

Our new knowledge shows us that, after childbirth, higher numbers of women who are breastfeeding are becoming infected with HIV and hence passing the virus on to their children. Models had not fully captured the length of time for which women breastfed and were therefore at risk of passing on the virus through their milk if they became infected with HIV. With the model adapted to take into account women breastfeeding for longer than one year, the number of infants contracting HIV increased slightly for all years since the start of the epidemic.

Because of such finetuning, estimates from one year can’t be compared with estimates from a previous year. When UNAIDS publishes its yearly data, we revise all previous years’ estimates, taking into account the revised methodology. For example, the estimate published in 2006 for the worldwide number of people living with HIV in 2005 was 38.6 million—this was before we had incorporated national household surveys into estimates. By 2016, with the additional information from surveys, the number for 2005 had been revised to 31.8 million. Likewise, the estimate for AIDS-related deaths in 2005 was 2.8 million, which, by 2016, had been revised down to 2.0 million in 2005.

This finetuning has steadily improved the accuracy of our estimates, with the result that recent revisions are becoming smaller—the estimated number of people living with HIV in 2013 made in 2014 was 35.0 million, not far off the current estimates of 35.2 million.