HIV trials

Press Statement

The end of the Mosaico vaccine trial must be a spur to deliver HIV treatment and prevention options to all who need them says UNAIDS

23 January 2023 23 January 2023GENEVA, 23 January 2023— The end of the Mosaico HIV vaccine trial must lead to a continued drive to innovate as well as an urgency to ensure that proven HIV prevention and treatment options reach all who need them, says UNAIDS. Rapid progress against the HIV pandemic is possible if existing prevention and treatment options are made available through the sharing of technologies, expanding provision, and tackling barriers to access. The development, and sharing, of long-acting prevention and treatment options are also important to expand coverage.

“The disappointment of the vaccine trial further underlines the importance of rolling out available HIV treatment and prevention innovations, including oral PrEP, long acting injectables and the vaginal ring,” said UNAIDS Executive Director, Winnie Byanyima. “The search for a vaccine must continue, but it’s important to remember that despite this setback the world can still end AIDS by 2030 by delivering all the proven prevention and treatment options to all the people who need them.”

Although there were no safety concerns flagged during the vaccine trial, it is being discontinued after an independent review of the research found no evidence of reduced risk of HIV infection among participants. The trial began in 2019 as a private-public partnership that included the United States National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Janssen Vaccines & Prevention B.V., the HIV Vaccine Trials Network and the United States Army Medical Research and Development Command. The trial enrolled 3900 men who have sex with men and transgender people across eight countries in Europe and the Americas, including the United States. Participants received four injections over 12 months, either of the vaccine or a placebo, with the monitoring board finding no significant difference in the HIV acquisition rate between the two groups.

Global research efforts into vaccines and a cure must carry on. At the same time, the world cannot wait for, or depend on, a vaccine or cure. The end of AIDS by 2030, as promised, is still possible, but leaders have no time to wait.

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Related

Documents

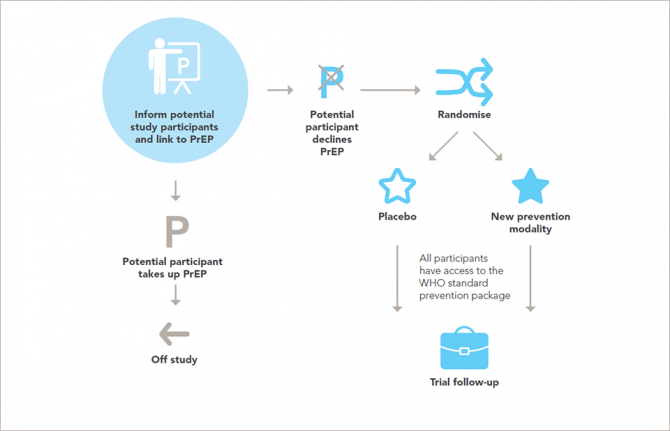

Ethical considerations in HIV prevention trials

27 January 2021

UNAIDS and the World Health Organization have published this updated guidance on ethical considerations in HIV prevention trials. The new guidance is the result of a year-long process that saw more than 80 experts and members of the public give inputs and is published 21 years after the first edition appeared. Read the story announcing this guidance This document is also available in Portuguese.

Related

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

A shot at ending AIDS — How new long-acting medicines could revolutionize the HIV response

21 January 2025

Feature Story

An HIV vaccine: who needs it?

21 July 2021

21 July 2021 21 July 2021The participants of the International AIDS Society (IAS) Conference on HIV Science session on an HIV vaccine were welcomed by Lucy Stackpool-Moore, Director, HIV Programmes and Advocacy at the International AIDS Society, after which Susan Buchbinder, from the University of California, San Francisco, and the San Francisco Department of Public Health, made introductory remarks. Two recorded presentations were then shown, by Kevin De Cock and Gabriela Gomez, speaking, respectively, on the need for and role of an HIV vaccine and on modelling science around the requirements and impact of a putative vaccine.

UNAIDS’ Science Adviser, Peter Godfrey-Faussett, then moderated a lively panel discussion that included Yazdan Yazdanpanah, Kundai Chinyenze, Rachel Baggaley, Daisy Ouya, Jerome Singh and Paul Stoffels.

The first question was on whether a vaccine for HIV, if it arrived, would be too late in view of the other HIV prevention modalities available. The consensus was that a vaccine is still needed, especially in low- and middle-income countries and for key populations. The participants then discussed how good a vaccine would need to be. Relevant issues include efficacy and durability, but a priority is proof of concept of activity. The participants acknowledged that initial inconvenient dosing schedules are justified if it can be shown that a product is protective. Minimum efficacy probably needs to be in the region of 50–60% for products to be taken forward.

The discussion also covered engagement by big pharma—Johnson & Johnson is currently the major company pursuing HIV vaccine research, in conjunction with diverse governmental, nongovernmental and clinical partners. It was emphasized that people and individual motivations drive the science, both for HIV prevention and treatment.

Inevitably, the comparison of vaccine development for COVID-19 and HIV came up. The panellists emphasized, however, that the reasons for a lack of success so far in HIV was largely related to the complex nature of HIV itself.

The discussion ended on a note of realistic optimism, with acknowledgment of the benefits of scientific investment in HIV vaccine research to date, including for COVID-19, but with recognition that long-term commitment is still required. The results of the two ongoing phase three trials (Imbokodo and Mosaico) are eagerly awaited.

Quotes

“A vaccine would not be too late; it would be key to getting back on track.”

“For a comparison group in a phase three trial, the “standard of prevention” is a key question.”

“A world without HIV needs a vaccine.”

“We need advocacy for vaccine research in a changing prevention landscape.”

Feature Story

How was a COVID-19 vaccine found so quickly?

09 February 2021

09 February 2021 09 February 2021As COVID-19 vaccination begins around the world, UNAIDS spoke to Peter Godfrey-Faussett, UNAIDS Senior Science Adviser and Professor of International Health and Infectious Diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, about what is holding up an HIV vaccine.

Many people are asking, “How was a COVID-19 vaccine found so quickly?”

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, which is the virus that causes COVID-19, jumped from animals into humans in 2019. Whereas for HIV, that jump occurred 100 years ago in around the 1920s, and it became a problem in the 1980s when it started spreading among humans to a much greater extent.

The reason we’ve seen such a push on the COVID-19 vaccine is because of the urgency. In 2020, COVID-19 has infected almost 100 million people on the planet. COVID-19 has already killed 2 million people in 2020.

So, this urgency comes about, despite the fact that we’ve seen dramatic changes in everybody’s life, with changes to travel and social distancing and masks and hand washing and sanitizer, and yet we've still seen a rapid rise in infections. This produces a huge urgency to make a vaccine. And, of course, it has a massive economic impact.

HIV and SARS-CoV-2 are quite different, right?

There are fundamental differences between SARS-CoV-2 and HIV. Although they are both viruses, SARS-CoV-2 is a very simple infection. The disease can be complicated, and sometimes mysterious, but almost everyone infected with SARS-CoV-2 develops antibodies to the spike protein and this neutralizes the virus and leads to recovery with a clearance of the virus.

In contrast, almost everybody infected by HIV develops antibodies and we use those antibodies in regular HIV tests. But, unfortunately, very few clear the infection and those antibodies are not sufficient to neutralize the HIV. The HIV envelope, which is more or less like a spike, is a complex structure on the surface of the virus. It’s coated with sugars and the active site is deep inside, so it’s hard to engage with it.

Over time, as people are infected with HIV some people do develop antibodies able to neutralize HIV, but that can take many years, and furthermore HIV is a retrovirus—that’s why we talk about antiretrovirals. A retrovirus is a virus that copies its genetic code and integrates it into the human genetic code. And as it copies, it copies its genetic code, but it doesn’t do it accurately, it makes many mistakes. What that means is that the envelope protein and the HIV itself is constantly changing, shifting its shape, making it difficult for antibodies to protect against it, so even the neutralizing antibodies from one individual often fail to neutralize the virus from a different individual.

We have now found some so-called broadly neutralizing antibodies, as in antibodies that neutralize many different strains of HIV. And those are the antibodies that people are studying at the moment and trying to see whether or not they protect people from catching different strains of HIV. They could be an important part of the process for developing a vaccine against HIV if we could get broader neutralizing antibodies to be generated before the HIV infection occurred.

Finally, we have to remember that, unlike COVID-19, or maybe partly unlike COVID-19, HIV depends a lot on T-cells—the other half of the human defence system. The human immune system has antibodies, but it also has so-called cellular immunity, which is led by T-cells, and that’s much harder to study and much more varied and it also makes HIV difficult and different from COVID-19 when it comes to developing a vaccine.

How much money is being invested in HIV vaccines?

Each year for the past decade we’ve invested around US$ 1 billion in research and development to try to produce an HIV vaccine. Is that a lot or is it not enough? It’s about 5% of the global HIV response budget. There has been some limited success. Back in 2009 there was great excitement when a vaccine candidate in Thailand did produce some protection against HIV infection, but not enough for it to be taken into widescale production.

And then over the next decade, subsequent trials have taught us a lot about the immunology, about the way human bodies and immune systems interact with HIV, but they haven’t led to a reduction in new HIV infections. Hope is currently resting on two large studies that are in the field at the moment, and there are many other candidates in the pipeline. So, I think there is hope, but we clearly won’t have a vaccine in the short term in the way that we have with COVID-19.

COVID-19 has taken the headlines—what about other infectious diseases?

In Africa, tuberculosis, malaria and HIV each kill more than five times as many people per year as COVID-19 has killed in Africa this year. These are huge problems and they've been going on for a long time. We have a vaccine against tuberculosis, the BCG vaccine, first used 100 years ago, starting in 1920, but unfortunately it doesn't really protect against the common adult forms of tuberculosis. Just recently, new vaccines have been discovered against both tuberculosis and malaria, but they don’t work particularly well. There are discussions about whether to scale them up because they only have a protective efficacy of 30% or less.

The good news is that a new malaria vaccine has just gone into big phase three trials in Africa, and in fact it’s produced by the same setup that has produced the AstraZeneca Oxford COVID-19 vaccine, so the hope is that the research that’s being done on COVID-19 vaccines may act as a shot in the arm for all the other important infectious disease killers that actually kill many, many more people in Africa and other resource-constrained parts of the world.

Watch: UNAIDS Science Adviser explains some differences between HIV and COVID-19

Watch: UNAIDS Science Adviser explains some differences between HIV and COVID-19

Our work

Feature Story

New guidance on ethical HIV prevention trials published

27 January 2021

27 January 2021 27 January 2021UNAIDS and the World Health Organization have published updated guidance on ethical considerations in HIV prevention trials. The new guidance is the result of a year-long process that saw more than 80 experts and members of the public give inputs and is published 21 years after the first edition appeared.

“UNAIDS is committed to working with the people and populations affected by HIV, promoting and protecting their rights,” said Peter Godfrey-Faussett, UNAIDS Science Adviser. “This guidance sets out how to carry out ethical trials on HIV prevention while safeguarding the participants’ rights during scientific research and promoting the development of new HIV prevention tools.”

With 1.7 million people becoming newly infected with HIV in 2019, there is still an urgent need to develop new ways of preventing HIV and make them available so that people can protect themselves from the virus. While new methods of preventing HIV have been developed over the past few years, for example pre-exposure prophylaxis, taken orally, in the dapivirine ring or in long-acting cabotegravir injections, the demand for easy-to-use and effective HIV prevention tools remains strong.

However, the need to develop new HIV prevention methods needs to be balanced with the need to protect the people who participate in scientific studies of the safety and efficacy of the prevention tools.

Research on people is governed by a well-established framework of ethical standards. The new report sets out in 14 guidance points the ethical standards for research on HIV prevention and upholds and explains the universal principles of ethics for research involving people in ways that are relevant to the participants and to developments in research for HIV prevention.

“The World Health Organization must ensure that policymakers and health implementers keep ethics at the heart of their decision-making. This collaboration with UNAIDS in convening a wide range of stakeholders for the review is a model for the future development of ethics guidance,” said Soumya Swaminathan, Chief Scientist at the World Health Organization.

The ethical considerations surrounding HIV prevention research are complex. Research must be conducted with the populations for which the new methods might have the most impact—such as key populations and adolescent girls and young women in locations where there is a high incidence of HIV—but members of those populations often live in situations that make them vulnerable to discrimination, incarceration or other harm, which can limit their participation in research and makes ethical research more challenging. The updated guidance seeks to set out how to ethically incorporate the needs of the people who could most benefit from HIV prevention research.

The updated guidance includes a number of key revisions to the previous edition. The importance of community members being involved at all stages of research projects is highlighted—there must be an equal partnership among research teams, trial sponsors, key populations, potential participants and the communities that live in settings where trials are taking place.

The issue of fairness, with an inclusive selection of study populations without arbitrary exclusion on the basis of characteristics such as age, pregnancy, gender identity or drug use, is emphasized. The guidance also underlines contexts of vulnerability—people and groups should not be labelled as vulnerable, but rather the emphasis should be on the social or political contexts in which people live that may render them vulnerable.

That researchers and trial sponsors should, at a minimum, ensure access to the package of HIV prevention methods recommended by the World Health Organization for every participant throughout the trial and follow-up is set out in the updated guidance, along with the need for post-trial access by participants to products that are shown to be effective.

“This revised guidance will support all stakeholders in designing and conducting ethically and scientifically sound HIV prevention trials that advance the AIDS response towards the goal of zero new HIV infections,” added Mr Godfrey-Faussett.

This guidance document is also available in Portuguese.

Our work

Feature Story

HIVR4P 2018 highlights new possibilities for HIV prevention

31 October 2018

31 October 2018 31 October 2018The possibilities for new and improved HIV prevention options were showcased at the recent HIV Research for Prevention (HIVR4P) conference, although the participants heard that many new tools are still several years from being ready for implementation.

The importance of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), including PrEP delivered by a vaginal ring and long-acting PrEP, including injectable PrEP, was featured in many presentations. Vaginal ring PrEP offers better female-controlled prevention options that can protect women without their partner’s knowledge, while injectable PrEP would mean that daily pill-taking and the risk of forgetting to take the pill would be history. Both vaginal ring PrEP and long-acting PrEP are still some way from being available, however, with the vaginal ring currently being reviewed for regulatory approval by the European Medicines Agency and trials for long-acting PrEP not due to deliver results until 2021 or later.

If antibodies and engineered molecules that mimic them can be shown to prevent HIV infection, the way to six-monthly injections for either prevention or treatment could be opened up, along with the possibility of a vaccine that made people develop their own similar antibodies. The participants heard that much progress had been made in discovering and developing such antibodies. The first proof of principle trials showing their effectiveness will report their results in 2020.

“Science has delivered us extraordinary advances in technologies for the diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of HIV infection. There is now real excitement that over the next years it will also lead to effective affordable prevention tools,” said Peter Godfrey-Faussett, Science Adviser, UNAIDS.

The participants heard that there are high levels of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among the populations at higher risk of HIV and that, as we have known for decades, STIs lead to increased HIV acquisition. The rates of the major treatable bacterial STIs have been rising steadily and are at alarming levels among gay men and other men who have sex with men and young people in eastern and southern Africa, in part due to declining condom usage. The high rates of the major treatable STIs have become particularly evident with the advent of increased screening accompanying the roll-out of PrEP.

Many STIs have no symptoms and can only be diagnosed with modern diagnostic tests—these are simple, but still far too expensive for the countries that need them the most. Along with geography and age group, STIs are among the strongest indicator of risk of HIV. An integrated STI and HIV prevention approach could offer PrEP to people who are HIV-negative but have an STI and live in an area where HIV is prevalent.

New prevention technologies are likely to be relatively expensive and hence will need to be focused on populations at higher risk in order to be affordable and cost-effective. Mathematical modelling shows that these new HIV prevention technologies may have only a limited impact on new HIV infections in eastern and southern Africa. For example, modelling of the impact of the dapivirine ring—a vaginal ring with a slow release of an antiretroviral medicine that protects against HIV infection—shows that only 1.5–2.5% of HIV infections would be averted over the next 18 years in Kenya, Uganda, Zimbabwe and South Africa. With the cost of averting one HIV infection through the use of the dapivirine ring varying from US$ 10 000 to US$ 100 000, many of the participants argued for integrating and combining both HIV treatment and prevention, and the responses to HIV and other diseases, for maximum effect.

The biennial HIVR4P conference was held in Madrid, Spain, from 21 to 25 October.

Feature Story

Global HIV prevention targets at risk

29 October 2018

29 October 2018 29 October 2018As the world grapples with how to speed up reductions in new HIV infections, great optimism is coming from the world of HIV prevention research with a slate of efficacy trials across the prevention pipeline. Major HIV vaccine and antibody efficacy trials are under way, as is critical follow-on research for proven antiretroviral-based prevention options.

However, a new report by the Resource Tracking for HIV Prevention R&D Working Group shows that rather than bolstering the new research by increasing investments into these exciting new advances, resources for HIV prevention research and development are actually slowing down.

In fact, in 2017, HIV research funding declined for the fifth consecutive year, falling to its lowest level in more than a decade. In 2017, funding for HIV prevention research and development decreased by 3.5% (US$ 40 million) from the previous year, falling to US$ 1.1 billion.

“Make no mistake, we are in a prevention crisis and we cannot afford a further funding crisis,” said Mitchell Warren, AVAC Executive Director. “It is unacceptable that donor funding for HIV prevention research continues to fall year after year even as research is moving new options closer to reality. We need continued and sustained investment to keep HIV prevention research on track to provide the new tools that will move the world closer to ending AIDS as a public health threat.”

The report warns that meeting the UNAIDS HIV prevention Fast-Track target of less than 500 000 new infections by 2020 (new HIV infections were at 1.8 million in 2017) will not only require the expansion of existing options such as voluntary medical male circumcision and pre-exposure prophylaxis, but also the development of innovative new products, including long-acting antiretroviral-based prevention options and a vaccine.

Indeed, sustained funding will be critical to keep the full gamut of HIV prevention research moving forward in a timely manner, as even small declines in funding could delay or sideline promising new HIV prevention options that are needed to end the AIDS epidemic.

“With 5000 people becoming infected with HIV every day, it is critical that we both scale up the effective HIV prevention programmes we currently have and invest in new technologies and solutions so that they can become a reality for the populations most affected by HIV,” said Tim Martineau, UNAIDS Deputy Executive Director, a.i. “Doing both will avert new infections, save lives and reduce the rising costs of life-long antiretroviral treatment.”

The Government of the United States of America continues to be the major funder of HIV prevention research, contributing almost three quarters of overall funding in 2017. However, this was also a decrease of almost 6%, bringing funding from the United States to a five year low of US$ 830 million. The report highlights that the uncertainty around continued political will to fund the AIDS response is a serious concern.

This week, researchers, implementers, advocates and funders are gathering at the HIV Research for Prevention (HIVR4P 2018) conference in Madrid, Spain, to review progress in HIV prevention research. There is much to be optimistic about in HIV science and in the accumulated knowledge of how to end the epidemic; however, the sobering changes in the funding and policy environments are raising some serious concerns about the future of the response to HIV and the world’s ability to respond to the continued challenges that HIV presents.

The report and infographics on prevention research investment are online at www.hivresourcetracking.org and on social media with #HIVPxinvestment.

Since 2000, the Resource Tracking for HIV Prevention R&D Working Group (formerly the HIV Vaccines & Microbicides Resource Tracking Working Group) has employed a comprehensive methodology to track trends in research and development investments and expenditures for biomedical HIV prevention options. AVAC leads the secretariat of the working group, which also includes the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and UNAIDS.

Report and infographics on prevention research investment

Feature Story

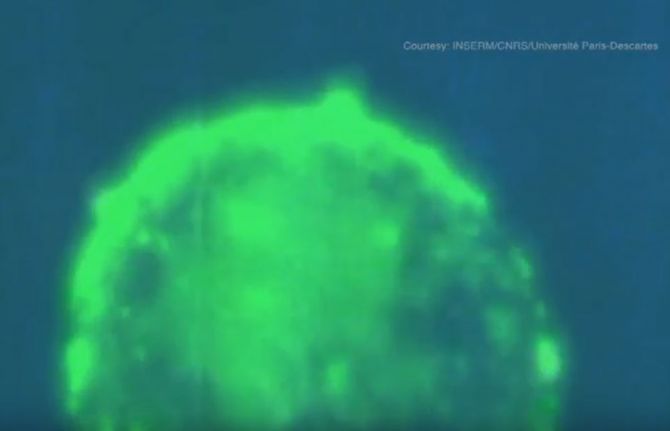

HIV transmission filmed live by French scientists

28 May 2018

28 May 2018 28 May 2018A team of French researchers has succeeded in filming HIV infecting a healthy cell. UNAIDS spoke to Morgane Bomsel, Research Team Director at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), about the feat.

What motivated you to film HIV transmission?

Morgane Bomsel: HIV transmission has not been studied much and we had no precise idea of the exact sequence of events leading to HIV infection of genital fluids during sexual intercourse. Neither did we know how immune cells are infected and what the consequences are. The vast majority of new HIV infections are acquired via the genital and rectal mucosa; however, the outer layer, the epithelium, of those tissues varies and affects how HIV enters the body.

What were the challenges?

MB: The challenges involved building an experimental model that mimicked genital mucosa infected by genital fluids suitable for live imaging. We reconstructed in vitro human male urethral mucosa based on human cells, the surface of which had been engineered to be red, and an infected white blood cell (a T lymphocyte, the main infectious element in sexual fluids) that was engineered to be fluorescent green and in turn would produce fluorescent green HIV infectious particles.

We had to render the system fluorescent to be able to visualize it and track HIV entry in the mucosa by live fluorescent scanning. Finally, we had to devise a system to allow the microscope lens to visualize the contact between the cells. All of this, of course, was done in an extremely secure setting and all of us were wearing two pairs of gloves and a hat, a coat, glasses and a mask.

When did you know you had a breakthrough?

MB: Our eureka moment was when we captured on film the spillage of a string of viruses, like a gun showering bullets. This lasts for a couple of hours and then, as if the infected cell has lost interest, it detaches itself and moves on.

Please walk us through the video

MB: The HIV-infected cells are labelled in green and produce fluorescent viruses that appear as green dots.

What we see is the HIV-infected cell attaching itself closely to the outer layer, the epithelium, of healthy reconstructed cells of a genital tract mucosal lining.

White blood cells of the immune system, macrophages, that usually engulf foreign substances, debris or cancer cells are seen engulfing the red particles slightly moving next to the blue macrophage nucleus.

The HIV-infected cell approaches the surface of the mucosa and places itself gently on the surface. Owing to, or induced by, contact, the infected cell recruits preformed viruses towards the cell contact (the intense yellow green patches) and then starts to spit those preformed viruses as full infectious viruses that appear as green dots.

These green viruses penetrate the outer layer of the tissue by a process called transcytosis—a type of transcellular transportation. The viruses enter the cell and exit, still infectious, at the other side of the epithelial barrier. As a result, HIV penetrates the types of white blood cells responsible for detecting, engulfing and destroying foreign substances and infects them. Once inside the nucleus, the virus inserts itself in the genetic material, the DNA, and the blood cells that are meant to protect the body start to produce viruses.

Interestingly enough, the video showed that the production of viruses does not last very long. After three weeks, the infected white blood cells become dormant and a reservoir of white blood cells is formed.

What makes HIV particularly tricky to cure?

MB: Attempts to cure HIV have been very difficult because of the dormant infected white blood cells. Those cells are hard for the immune system to find and kill, and for the scientist to study. Antiretroviral medicines prevent the virus from spreading throughout the body and the immune system targets cells that are actively transcribing viral DNA. But because of the reservoir, these cells become a problem if a patient stops taking antiretroviral therapy. They can slowly awaken, allowing the virus to replicate freely.

Related links

Related

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

U=U can help end HIV stigma and discrimination. Here’s how

27 February 2025

Press Statement

UNAIDS welcomes preliminary trial results that could offer women a new HIV prevention option

07 March 2018 07 March 2018GENEVA, 7 March 2018—UNAIDS welcomes mid-way results from two studies that show that a vaginal ring releasing long-acting antiretroviral medicine to prevent HIV is up to 54% effective in preventing HIV infections among women. The ring, which is replaced monthly, slowly releases the antiretroviral medicine dapivirine and could give women an additional HIV prevention option that is discreet and that they can control.

“These results are significant,” said Michel Sidibé, Executive Director of UNAIDS. “Structural, behavioural and biological factors make women more vulnerable to HIV infection, so it is extremely important that they have the opportunity to protect themselves from HIV, on their own terms.”

The interim results are from two large open-label studies—studies in which the participants know which medicine is being used; that is, no placebo is used—conducted in South Africa and Uganda. The trails enrolled women between the ages of 20 and 50 years.

The HOPE trial, which began in August 2016 and enrolled more than 1400 women by October 2017—the time of the interim review—found a 54% reduction in HIV risk. This means that the rate of new HIV infections was 1.9 women newly infected for every 100 participants in a given year; based on statistical modelling, the researchers determined that the rate of new infections would have been 4.1 for every 100 had the women not been offered the ring. The DREAM trial, which enrolled 940 women from July 2016, had similar findings, with a 54% reduction in the HIV incidence rate. The final results from both studies are expected in 2019.

Adherence was shown to be high in both of the trials, although the measures of adherence were not able to determine whether the women used the ring all of the time, most of the time or just some of the time. The DREAM study showed that more than 90% of the women in the study used the ring at least some of the time, based on residual drug levels, and the HOPE study showed that 89% of returned rings indicated that the ring was used at least some of the time within the previous month.

This is the first time that efficacy of more than 50% has been observed in HIV prevention trials involving only women. Two previous phase III trials presented in 2016—ASPIRE/MTN-020 and the Ring Study/IPM 027—which did include a placebo group showed only modest protection (30%) against HIV infection for women. Women from both ASPIRE and the Ring Study were included in the HOPE and DREAMS trials.

Other scientific advances in HIV prevention presented in recent years include the PROUD and IPERGAY studies, which in 2015 reported an 86% reduction in HIV acquisition among HIV-negative men who took antiretroviral medicines to prevent HIV, the 2011 HPTN 052 trial announcement, which showed that early initiation of antiretroviral therapy can reduce the risk of transmission to an uninfected partner by 96%, and the 2011 Partners PrEP and TDF2 studies, which showed that a daily antiretroviral pill taken by people who do not have HIV infection can reduce their risk of acquiring HIV by up to 73%. The South Africa Orange Farm Intervention Trial, funded by the French Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA (ANRS) and published in 2005, demonstrated more than a 60% reduction in HIV infections among circumcised men.

“These important breakthroughs show just how critical it is to continue to invest in research and development into new and effective HIV prevention options,” said Mr Sidibé. The latest reports show that in 2016 funding for HIV prevention research and development was its lowest level in a decade, with no indications that investments are set to increase.

UNAIDS stresses that despite the recent scientific discoveries, there is still no single method that is fully protective against HIV. To end the AIDS epidemic, UNAIDS strongly recommends a combination of HIV prevention options. These can include the correct and consistent use of male or female condoms, waiting longer before having sex for the first time, having fewer partners, voluntary medical male circumcision, avoiding penetrative sex, the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis for people at higher risk of HIV infection and ensuring that all people living with HIV have immediate access to antiretroviral medicine.

In 2016/2017* an estimated:

*20.9 million people were accessing antiretroviral therapy in June 2017

36.7 million [30.8 million–42.9 million] people globally were living with HIV

1.8 million [1.6 million–2.1 million] people became newly infected with HIV

1.0 million [830 000–1.2 million] people died from AIDS-related illnesses

UNAIDS

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) leads and inspires the world to achieve its shared vision of zero new HIV infections, zero discrimination and zero AIDS-related deaths. UNAIDS unites the efforts of 11 UN organizations—UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank—and works closely with global and national partners towards ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. Learn more at unaids.org and connect with us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube.

Press centre

Download the printable version (PDF)