Feature Story

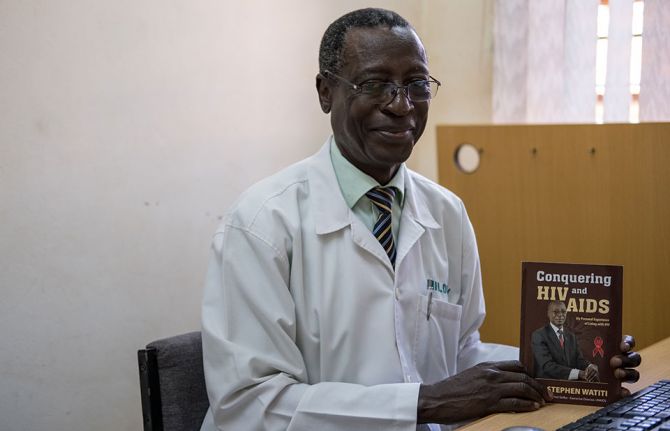

Stephen Watiti: a personal journey that imprints on others

27 November 2020

27 November 2020 27 November 2020Nearly 40 years into the HIV response, improved access to HIV treatment means the 26 million people living with HIV globally who are on HIV treatment can live long and healthy lives. But what does health care for an ageing population of people living with HIV look like?

Having lived with HIV for more than 30 years, this is a question 66-year-old Stephen Watiti from Uganda has been considering.

“My needs are going to be changing … and in the future most of the people living with HIV will be 50 years and above,” said the celebrated medical doctor, who is based at Mildmay Uganda Hospital, in Kampala.

In the eastern and southern Africa region, approximately 3.6 million of the 20.7 million people living with HIV are over the age of 50 years.

The new UNAIDS World AIDS Day report, Prevailing against pandemics by putting people at the centre, calls for a differentiated HIV response that is more intensive and more effective at ensuring that we reach those who until now have been left behind. This includes expanding treatment access equitably by providing people-centred, age-sensitive and integrated health services.

People living with HIV should be supported to lead long and healthy lives and people over 50 years of age should have equal access to social protection, employment and social integration.

Mr Watiti said little attention has been given to this phenomenon. “We have worked a lot in paediatric HIV. In geriatric HIV, there is no person who is trained in preparation for that,” he said.

Back in 1999, a period void of HIV treatment and substantial HIV knowledge and training among people in eastern and southern Africa, Mr Watiti experienced multiple AIDS-related illnesses. He had a “frightening” near-death experience where his CD4 count plummeted. His ailing body had to battle tuberculosis, cryptococcal meningitis and Kaposi’s sarcoma—all at the same time.

Mr Watiti started HIV treatment in 2000. However, due to the affordability and accessibility of the antiretroviral medicines in his regimen at that time, his adherence was poor, and he fell sick due to treatment failure.

In 2003, with a new antiretroviral regimen, and the unwavering support of a counsellor from the AIDS Support Organization in Uganda, Mr Watiti realized he was “no longer dying.”

During this period, he realized the need for him to educate and inspire his patients living with HIV. And so he returned to work.

Mr Watiti has come a long way. Despite living with uncertainty as part of an older generation living with HIV, Mr Watiti intends to live a full life, practising medicine well into his seventies.

“I’ll have to keep swallowing this medicine unless there’s a cure by then,” he said.

However, Mr Watiti wants to know what can be done to ensure that people living with HIV who are on treatment have a good quality life, including access to mental health services.

This is a question he raised during a conversation with UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima at the launch of the UNAIDS World AIDS Day report.

Ms Byanyima agreed. “Considering that someone is going to live off a tablet for the rest of their lives and sometimes that person is living in poverty or hiding their secret because of stigma, this is a huge challenge of the mental and emotional well-being of a person,” she said. “People living with HIV need a wider comprehensive package of services, including mental health. The AIDS response cannot be narrowed just to the tablet.”

Mr Watiti was a beacon of hope for people who were living with HIV at a time when surviving AIDS was a grim prospect and is an example of resilience for people living with HIV today.

Mr Watiti says as he counsels his patients to overcome HIV stigma and about the importance of diligently taking their medication, it was as if he was talking to himself: “To tell you the truth, if there’s one person I've helped the most, it is me.”