Feature Story

“Someone has to start”: how a Haitian transgender activist is inspiring hope through visibility

09 November 2020

09 November 2020 09 November 2020Haiti’s first safe house for transgender people opened last week. Kay Trans Ayiti launched with the snip of a red ribbon and cheers from a circle of activists and residents. The group took turns taking pictures between bobbing pink and blue balloons tied to the veranda.

The triumphant moment came during a tough time. Asked how transgender people have fared in Haiti during COVID-19, home founder Yaisah Val was emphatic. “When the rest of the population has a cold, the trans community has pneumonia. Just imagine that with the hunger, poverty and meagre resources in Haiti, we are always on the outside,” she says.

In many ways, Ms Val is not as shut out as the people she serves. Haiti’s first publicly open transgender woman introduces herself as a mother of two and a wife. She has a degree in education and clinical psychology. She was a teacher and school counsellor before becoming a full-time community mobilizer, activist and gender identity spokesperson. During what she calls her stealth years, she was easily accepted as a woman.

Born in the United States of America to Haitian parents, she has had the benefit of a stable home, supportive teachers and a wildly loving grandmother.

“If you are going to be a sissy you will be the best sissy there is because you are mine,” her granny told her when she was a boy named Junior.

This is an anomaly. According to the United Caribbean Trans Network, transgender people in the region are far less likely to be supported by family, complete their secondary education and be employed. They are more likely to be homeless, to sell sex to survive and to face extreme violence. All this sharply increases the community’s HIV risk. A recent study found that transgender women in Haiti had an HIV prevalence of 27.6%—14 times higher than the general population.

But notwithstanding her “privileged” life, Ms Val’s 47-year journey has been fraught.

From when she was two or three years old she knew she was a girl. The gender policing from relatives was immediate and incessant: “Straighten up that boy. You can’t let him grow up like that.” At seven she was admitted to Washington Children’s Hospital with self-inflicted wounds to her genitals. Puberty was, “hell … a lot of confusion and self-hate.”

About 20 years ago she became herself during the Haitian Carnival. She braided her hair, slipped into a dress and boarded a loud, colourful tap-tap bus with her friends. One man flirted. He called her pretty and opened doors. She felt like Cinderella.

“That boy eventually found out and beat me within an inch of my life,” Ms Val remembers. “Whether you are upper class or middle class or on the streets, as long as you are trans it does not matter. Once you disclose, all respect is gone … you are just this thing. That one word disarms you of all humanity in people’s eyes.”

Transitioning offered a sort of freedom, “I was living and being seen as who I am, who I had always been.” But the fear of being assaulted or excluded made her identity a stressful secret. Old boyfriends did not know she was transgender until she came out years later. She only disclosed to the man who would become her husband after they had lived together for a year and were on the brink of getting married.

“I don’t recommend people do that,” Ms Val says again and again, referring to transgender people hiding their gender identity from romantic partners. “It can be violent. It can be dangerous.”

In her case it worked out. Her partner decided that she was the same person he knew and loved. Three years ago, the story repeated when she disclosed to her children.

“I was just surprised,” her son, Cedrick said. “I was shocked in a good way. They’d slowly started educating me over the years, so I understood what it meant. Ever since then the whole mother/son bond went to a new level for both of us. It filled in all those gaps. Now everything made sense, like her childhood stories.”

Coming out to those closest to her has opened the floodgates to activism. In 2016, Ms Val became the first person in Haiti’s history to publicly identify as a transgender person. She has been a key partner for UNAIDS Haiti and the island’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people organizations. Last year she participated in a national dialogue on LGBTI rights. Together with her husband she started taking in homeless transgender people. That paved the way for Kay Trans Ayiti, which now houses 10 transgender people. Fundraising is under way for a programme of psychosocial support, hormonal replacement legal advice and job training. One of their employment initiatives is a food cart. Some of their residents are living with HIV. They are supported to remain adherent to their antiretroviral treatment.

Ms Val knows first-hand how terrifying it is to access sexual and reproductive health care as a transgender woman. She recalls the experience of going to a gynaecologist in Haiti to get a check-up related to her vaginoplasty. The doctor did not understand what “transgender” meant. That visit ended with the gynaecologist calling other doctors to gawk.

“I was a YouTube channel, a Google page … anything but a human being. I was upset. I was crying. This is why transgender people do not access health care! We have a lot of transmen with gynaecological issues who make herbal treatments rather than go to the doctor,” Ms Val says.

Her group, Community Action for the Integration of Vulnerable Women in Haiti (Action Communautaire pour l’integration des Femmes Vulnerable en Haiti, or ACIFVH), is working with two HIV clinics to sensitize health-care providers. Combatting the ignorance and conservatism is a tall task. Even after educational sessions some doctors and nurses have tried pushing their religious views on the trainers.

“I was lucky not to be hindered by transphobia and discrimination,” Ms Val reflects. “Imagine if I did not have a supportive grandmother, an education and opportunities. I would not have been the person you see now.

“If you throw a seed on concrete it is not going to thrive. Being trans is not the problem. It is the reaction people have to it: throwing them on the streets, not letting them work, not taking them into schools. We need to have a place in society. It is hard. It will take a while. But someone has to start.”

Our work

Region/country

Related

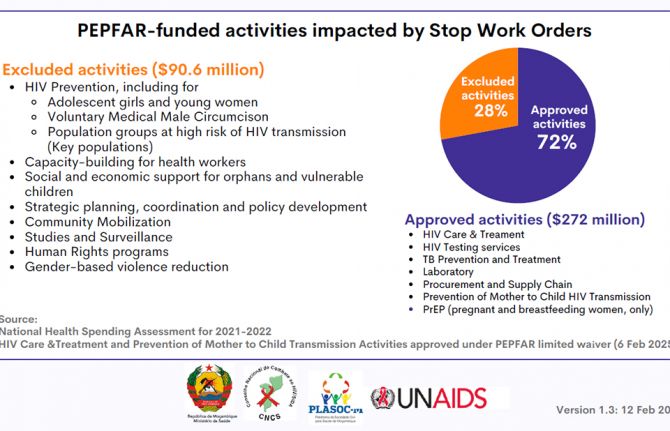

Impact of US funding freeze on HIV programmes in Haiti

Impact of US funding freeze on HIV programmes in Haiti

13 March 2025

Comprehensive Update on HIV Programmes in the Dominican Republic

Comprehensive Update on HIV Programmes in the Dominican Republic

19 February 2025