HIV trials

Feature Story

The role of women in HIV trials

05 December 2007

05 December 2007 05 December 2007

Decades after AIDS first became a global health

threat, it has become clear that gender has to be a

crucial consideration in medical research into

stopping the spread of HIV, and for treatment.

In the second of a three-part series on clinical trials and the search for effective HIV preventions and treatment, UNAIDS looks at why it is a scientific and ethical imperative that women and adolescent girls be adequately represented in testing and at the special issues that can surround their participation.

Women account for an increasing percentage of people living with HIV around the world. In sub-Saharan Africa, women and adolescent girls make up 61 percent of the 22.5 million people living with HIV, and young women in the 15-24 age group are three times more likely to become infected as men of the same age.

In high-income countries, some of the highest infection levels are to be found among women from ethnic minorities.

Decades after AIDS first became a global health threat, it has become clear that gender has to be a crucial consideration in medical research into stopping the spread of HIV, and for treatment. If investigators are to conduct research in those sectors of the population most exposed to HIV, which must be the case, then that means increasingly involving women, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa.

“It is important that HIV related research focus on the populations that are at most risk of HIV exposure,” said UNAIDS chief scientist Catherine Hankins.

Under-representation

Yet, until relatively recently, women were under-represented as participants in trials for all types of clinical interventions, including trials for HIV vaccines.

Thirty years ago the United States banned women of child-bearing age from taking part in initial phases of clinical trials. This step was taken in response to the thalidomide tragedy of the late 1950s and early 1960s when thousands of babies were born deformed in Europe. Their mothers had been prescribed thalidomide, a sleeping pill, to combat the effects of morning sickness during pregnancy.

Although the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulation officially referred only to women of child-bearing age, it effectively procluded all women from taking part in trials as even those unlikely to conceive, such as women using contraception, or who were infertile, celibate or lesbians. As a result, clinical trials for all preventions came to be dominated for several years, including the early 1980s which saw the recognition of AIDS as a global health danger, by the “cult of the 70-kilo man.”

Until relatively recently, women were under-

represented as participants in trials for all types of

clinical interventions, including trials for HIV

vaccines.

But scientists soon began to ask whether research findings based on all-male trials could confidently be applied to women – particularly given the physiological differences between men and women.

Women have a lower body mass, a higher body-fat content, and a hormonal cycle and different levels of hormones to men, all of which can affect drug action, or what is known as pharmacodynamics. There are also metabolic differences. Aspirin is a case in point. When taken in small daily doses, it has been shown to reduce the incidence of heart attack in men, but not in women.

Given the under-representation of women in trials, the US Congress was lobbied to revise the law. By 1993, the FDA had reversed its ban and produced guidelines calling for data to be analysed in terms of gender.

Physiologically different

Change did not come overnight. When the results of the first ever efficacy trial for an HIV vaccine – AIDSVAX -- were published in 1994, there were still only 309 women among the 5009 people that took part.

In contrast, in the recently stopped STEP trial of a Merck HIV vaccine candidate women accounted for 38 percent of the 3000 participants.

“Women and men are physiologically different, so results and conclusions from male-only studies cannot be assumed to be applicable to women,” said Hankins.

“It is both ethically and scientifically sound to enrol women in adequate numbers to be able to provide answers pertinent to them in all stages of human subject research,” she added.

Some of the most important recent breakthroughs in the response to AIDS have come in areas where only women can be participants. Mother-to-child transmission, where because of successful interventions infection rates have fallen as low as 1-2 percent in high-income countries, is the most obvious example.

Some of the most important recent breakthroughs

in the response to AIDS have come in areas where

only women can be participants.

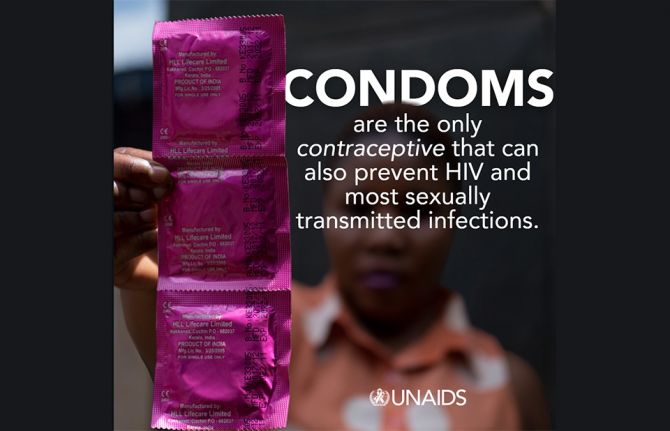

In fact, all the most promising biomedical HIV prevention intervention trials currently underway involve both men and women, with the exception of female-initiated prevention tools. These include microbicides and barrier methods including the new female condoms, which may potentially provide protection against HIV, STIs and pregnancy.

There are currently a number of microbicides – gels, creams, films, anti-HIV releasing rings – undergoing tests in various parts of the world. Some have already passed the stage of animal testing and moved on to efficacy studies in humans.

Women are also involved in phase 3 trials – the efficacy stage -- of pre-exposure prophylaxis, herpes simplex 2 suppression and treatment, and in all stages of HIV vaccine testing.

Gaps in research

For various reasons, women may be more susceptible to HIV infection than men. Studies of sexual partners where one is HIV-positive show that women are at least twice as likely to become infected through unprotected heterosexual sex than men.

The reason may be that the vagina has a large mucosal surface area, making it more vulnerable to the virus. Women are also exposed to a greater quantity of fluids by way of male semen.

Issues such as medication dosages, drug resistance, side effects stemming from sex-based differences need to be studied. Women have highter CD4 T-cell numbers—cells that initiate the body’s response to invading micro-organisms such as viruses—and their viral loads vary with CD4 T-cell counts in a different way to men.

Clinical trials need to be designed for safety of women, her foetus, breastfed infant, and in the case of vaginal or rectal microbicides, her partner. Safety and efficacy amongst women remains one of the gaps in current research.

Additional considerations

Vulnerability to HIV exposure is greater where women are marginalised due to their social, economic and legal status and this can influence their willingness, or ability, to take part in trials.

Women may fear being labelled within a community as an HIV risk, or be reluctant to take part because of concerns for possible harm to an unborn baby, or they may worry that it will affect their chances of getting pregnant in the future. These are important issues that researchers need to bear in mind and address when seeking to recruit amongst vulnerable communities.

Barriers for adolescent involvement

Biological distinctions between age groups must be

considered in research designed to assess safety,

immunogenicity and efficacy. But so far there have

been no HIV candidate vaccine trials involving

adolescents.

There also could be legal barriers to enrolling adolescents into trials for which they are assumed to be engaging in sexual activity.

One clinical issue for researchers is the physiological differences between women and adolescent girls. Sex hormone profiles change dramatically during adolescence and these changing sex hormones may have immunological consequences that may influence the efficacy of a given prevention tool, e.g. the immunological response to a vaccine.

Biological distinctions between age groups must be considered in research designed to assess safety, immunogenicity and efficacy. But so far there have been no HIV candidate vaccine trials involving adolescents.

There could be ancillary health advantages to involving older adolescent girls in clinical trials for female-initiated preventions such as female condoms and microbicides. These interventions can become part of routine sexual health practices and thus also give protection against other sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnanacies.

Sex workers

Female sex workers and injecting drug users are often isolated from the general population and so demand extra effort to ensure that they become participants in HIV-related research.

Current prevention methods for sex workers and injecting drug users may not work. Sex workers may not have easy access to condoms, or may be prevented from using them by the threat of violence or may receive more money for unprotected sex.

There are also questions about whether microbicides would be effective for high frequency use by women with multiple sex partners. So prevention research continues to be particularly important for them.

Furthermore, the precarious legal status of sex workers and female injected drug users may make participation difficult and could even expose them to increased exploitation.

Many of the most hope-inspiring avenues of

scientific study, notably microbicides, rely almost

exclusively on female trial participation.

Rightful place

In recent years, HIV research has begun to afford women the attention that their exposure to HIV would warrant. Many of the most hope-inspiring avenues of scientific study, notably microbicides, rely almost exclusively on female trial participation.

Nevertheless, women most at risk from HIV are often vulnerable to social, economic and cultural pressures that can complicate their involvement in trials.

“Women should be recipients of future safe and effective biomedical HIV prevention products and therefore should be eligible for enrolment in biomedical HIV prevention trials, both as a matter of equity and because in many communities throughout the world women, particularly young women, are at higher risk of HIV exposure,” said Hankins.

The question of HIV trials, and in particular the involvement of women and adolescent girls in them, will be the subject of a two-day conference being hosted by UNAIDS in Geneva December 10-11. On Friday 7 December, part three of this special web series will preview the Geneva meeting, featuring interviews with the four organizing partners UNAIDS, The Global Coalition on Women and Girls, Tibotec and the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW).

Links:

Three-part web series

Part 1: Meeting ethical concerns over HIV trials

Part 2: The role of women in HIV trials

Part 3: Experts meet on women and HIV clinic trials

More on biomedical research

HIV Prevention Research: A Comprehensive Timeline

Global Coalition on Women and AIDS

Tibotec

International Center for Research on Women (ICRW)

Publications:

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials (pdf, 750kb)

Good participatory practice guidelines for biomedical HIV prevention trials (pdf, 3.04Mb)

Feature Story

Meeting ethical concerns over HIV trials

03 December 2007

03 December 2007 03 December 2007In the first of a special three-part web series, www.unaids.org looks at the state of research into new HIV prevention technologies, the ethical debates around the issue, and the steps that have been taken to answer the concerns. The question of HIV trials, and in particular the involvement of women and adolescent girls in them, will be the subject of a two-day conference being hosted by UNAIDS in Geneva December 10-11.

Nearly three decades after AIDS began ringing global alarm bells, no vaccine is in sight and medical advances are still urgently needed. Some significant progress has been seen – biomedical prevention modalities which have been proven highly effective in randomised controlled trials, such as prevention of mother-to-child transmission and male circumcision for HIV risk reduction— still have suboptimal coverage in the most affected countries. Concerted efforts are underway to expand access to these two HIV prevention tools, however nevertheless, the prevention ‘tool box’ needs to be expanded to provide people with additional choices, particularly for prevention of sexual transmission of HIV.

But medical breakthroughs in such a complex disease not only take time—seeking them also poses special practical and, perhaps more critically, ethical problems because of the inevitable need for testing eventually to be done on humans. In recent years, there has been criticism from activist and human rights campaigners about perceived failings in the organisation of human trials. Argument has focused on suggestions of insufficient involvement of local communities in the low- and middle-income countries chosen as sites for testing in the decisions that surround trials, or on the alleged inadequacy of information or guarantees for volunteers taking part in them.

The often very public disputes that ensue have led UNAIDS and other international organisations involved in the AIDS response to refine guidelines for the ethical conduct of human trials.

Need as great as ever

According to the latest data released by UNAIDS and WHO, nearly 7,000 people are newly infected with HIV every day, while the daily death toll from AIDS stands at nearly 6,000 per day, putting it in the top rank of global killers. In sub-Saharan Africa, home to 22.5 million people living with HIV (68% of the global total), AIDS is the primary cause of premature death. Although scientists have succeeded in developing drugs that can prolong the lives of those living with HIV, only a minority of people in need of treatment in developing and middle-income countries has access to it.

Since their launch in 1996, antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) have revolutionised the treatment of HIV-related illness and prolonged and improved the quality of life for people living with HIV in countries where they are available and affordable. But in poorer countries, and particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where women and adolescent girls make up 61% of the population living with HIV, the cost of drugs remains a huge deterrent to their use, and this is particularly so of second line drugs which people need once first line regimens are no longer as effective for them. “Halting the spread of HIV remains an imperative as each new infection translates into eventual treatment demand. Finding ways to slow HIV transmission is a top research priority,” said UNAIDS Chief Scientific Adviser, Catherine Hankins. “Speeding the search for a biomedical breakthrough to complement changes in social norms and behaviours remains urgent.”

The International Aids Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) estimates that— conservatively—an effective HIV preventive vaccine could avoid almost 1-in-5 of a projected 150 million new infections – that is 30 million – in coming decades. A highly effective vaccine could prevent 70 million infections in 15 years, it says. Modelling of the potential impact of male circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa suggests that male circumcision could avert 2 million new HIV infections and 300,000 deaths over the next ten years and avert a further 3.7 million new HIV infections and 2.7 million deaths in the decade thereafter.

Trials underway

There are currently some 50 vaccine trials underway, or scheduled, in a record number of over 30 countries, ranging from the United States to Uganda. Much of the cutting-edge research is being carried out in Asia and Africa, where most of the new HIV infections are occurring. But the announcement in September 2007 of the discontinuation of a leading HIV Merck vaccine candidate being tested in trials underlines how difficult this type of research and development is and shows just how far there is still to go before a vaccine becomes available.

There are many other prevention strategies undergoing human testing. These include vaginal microbicides, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), suppression of herpes simplex 2 infection and treating the infected partner in serodiscordant couples to see if it reduces HIV transmission.

Vaginal microbicides come in the form of creams, gels, suppositories, films, sponges or rings that release anti-HIV microbicide over time and could afford protection against other sexually transmitted diseases. If spermicidal, they might also be used for preventing unintended pregnancy. The ideal product would be odourless and colourless. As such, microbicides could increase the options for women who find it difficult or impossible to persuade their partners to use a condom. PrEP is another experimental prevention strategy which is being tried out in many parts of the world. It consists of anti-retroviral medications, taken as a single drug or as a combination, on a daily basis, with the intention of protecting people from acquiring HIV.

The successes achieved so far in the response to AIDS, and future hopes for further advances, have and will depend on such human trials.

Scientists may get promising results in laboratory experiments and from studying animals, but at the end of the day, the only way to find out whether a biomedical HIV prevention strategy is effective, whether a vaccine triggers an immune response to impede or delay the development of disease, whether an intervention has side effects, and the frequency and severity of them, the implications for drug resistance, is to try the strategy out on people.

Protecting rights

Getting scientifically valid research requires that trials be carried out where there are sufficiently high numbers of infected people, and people at high risk of HIV exposure, and where effective interventions will have the greatest effect. This often means dealing with some of the most socially vulnerable sectors of society, whether they are women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa, sex workers, men who have sex with men or injecting drug users. And often, people most at risk may not be well placed to protect their rights in the run-up to and the preparation of testing, during the trial programme itself or in its aftermath.

A lack of information and the relative powerlessness of some communities could produce situations in which there is an unequal power relationship between research sponsors and trial investigators, on the one hand, and communities and trial participants on the other. People could, for example, opt to take part out of the false belief that there will be some immediate therapeutic benefit to them, which could even lead them to behave in a more risky fashion because they feel protected. Building research literacy and community capacity to engage meaningfully in trial design, conduct, monitoring and results dissemination is essential to minimising harms and maximising the benefits for communities of participation in research.

Ethical questions

One of the most controversial incidents in the history of AIDS research occurred in the early 1990s during testing of a shorter, simpler, and presumably cheaper version of perinatal zidovudine prophylaxis. Zidovudine was already known to be an effective barrier to the transmission of HIV from a mother to her unborn or newly born infant. The trials involved randomised placebo-controlled tests and were carried out in a number of developing countries. Activists argued that a placebo controlled trial amounted to a violation of fundamental ethical principles because those being given the placebo were being denied a treatment that had already proved its worth elsewhere. Zidovudine was one of the milestones in HIV research and had been shown to cut mother-to-child transmission by over 60%, offering tremendous hope to pregnant women. Subsequent improvements have reduced such transmissions in high-income countries to just 1-2 percent.

Another well-known incident surrounded randomised placebo-controlled trials for tenofovir disoproxil fumarate used as PrEP, in Cambodia and Cameroon in 2004-5. The Cambodian trial involving sex workers was halted by the government when no agreement was reached on future access to treatment for those who became infected during the trial. The affair generated much adverse news coverage and the Cameroon government followed suit in suspending the trial underway there.

In Thailand, a trial in which the participants were injecting drug users was criticised by activists for not providing clean needles. In one protest that gained much publicity, the activist group Act-Up Paris stormed the display stand of tenofovir’s manufacturer, Gilead, during the 2004 International AIDS Society Conference.

Health community responds

Much has been learned and acted upon from these experiences. For example, in 1993 the Council for International Organisations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) issued international ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects that stated that there was an ethical responsibility to provide treatment that conforms to the standard of care in the sponsoring country when possible.

In 2000 came the fifth revision of the Declaration of Helsinki with its stipulation that all those involved in studies be assured of the best “proven diagnostic and therapeutic method”. The same year saw publication of the UNAIDS guidance document “Ethical considerations in HIV preventive vaccine research” which has now been substantially revised in 2007 in collaboration with WHO and an expert panel to reflect changes, particularly changes in standard of prevention and access to care. “Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials” contains 19 guidance points for ensuring that scientifically rigorous biomedical HIV prevention trials meet ethical standards.

In 2005, following the tenofovir case, UNAIDS and others organised consultations focusing on ‘partnerships’ with communities, their involvement, standards of prevention and access to care. This led to UNAIDS producing in collaboration with AVAC “Good Participatory Practice Guidelines for Biomedical HIV Prevention Trials,” It covers core principles and essential activities throughout the research life-cycle, providing a foundation for community engagement in research.

“With solid international guidance in place for community engagement and the ethical conduct of trials, there is anticipation that research, both underway in the field and planned, can offer a number of promising new avenues to prevent HIV transmission, improve treatment and mitigate against the epidemic’s impact,” said Dr Hankins.

The question of HIV trials, and in particular the involvement of women and adolescent girls in them, will be the subject of a two-day conference being hosted by UNAIDS in Geneva December 10-11. On Wednesday 5 December, part two of this special web series will take a closer look at the history and debates around the involvement of women and girls in trials. Part three, to be published on Friday 7 December will preview the Geneva meeting, featuring interviews with the four organizing partners UNAIDS, The Global Coalition on Women and Girls, Tibotec and the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW).

Links:

Three-part web series

Part 1: Meeting ethical concerns over HIV trials

Part 2: The role of women in HIV trials

Part 3: Experts meet on women and HIV clinic trials

More on biomedical research

HIV Prevention Research: A Comprehensive Timeline

Global Coalition on Women and AIDS

Tibotec

International Center for Research on Women (ICRW)

Publications:

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials (pdf, 750kb)

Good participatory practice guidelines for biomedical HIV prevention trials (pdf, 3.04Mb)

Related

Press Statement

UNAIDS and WHO welcome new findings that could provide an additional tool for HIV prevention for men who have sex with men

23 November 2010 23 November 2010GENEVA, 23 November 2010––The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization (WHO) welcome new research published today showing that an antiretroviral drug combination, taken daily as a prophylaxis, in conjunction with use of condoms, reduces the risk of HIV infection by an average of 43.8% for HIV-negative men and transgender women who have sex with men.

UNAIDS and WHO congratulate the iPrEx study team for the exemplary conduct of this complex multi-site, multi-language trial.

Men who have sex with men are often marginalized, hard to reach, and have poor access to HIV prevention services. New data from 43 countries show that slightly more than half of such men benefit from HIV prevention programmes. In addition, nearly 80 countries criminalize same-sex relations.

“This positive result is going to give hope to millions of men who have sex with men and help them protect themselves and their loved ones,” said Michel Sidibé, UNAIDS Executive Director. “This new tool can be a valuable addition to current HIV prevention approaches and help bring about a prevention revolution.”

The iPrEx study enrolled 2499 men in six countries, primarily in South America. Volunteers who took a daily dose of tenofovir/emtricitabine (TDF/ FTC) as oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) were less likely to become infected with HIV than those who took the placebo. Those who took the pill consistently had higher effectiveness in preventing HIV infection.

"The trial opens exciting new prospects. It shows that oral pre-exposure prophylaxis can reduce the risk of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. We look forward to further examining these data to consider how we can best use this tool to enhance HIV prevention when used in combination with other prevention such as condom promotion in this population at higher risk," said Dr Margaret Chan, WHO Director-General.

The results from the study constitute proof of concept of the safety and partial effectiveness of oral PrEP. This study also showed the potential effects of combination prevention approaches—combining consistent condom use, frequent HIV testing, counselling, and treatment of sexually transmitted infections with pre-exposure prophylaxis for maximum prevention gains.

The announcement today complements results from the CAPRISA trial released earlier this year. That study found a vaginal microbicide gel containing tenofovir used before and after sex to be 39% effective in preventing new HIV infections in women.

The iPrEx trial is part of efforts to develop new HIV prevention options for people at risk of HIV exposure. In addition, on-going studies testing the use of similar drugs to prevent HIV infection will provide more safety and effectiveness data from diverse populations including heterosexual women, serodiscordant couples, and people who inject drugs.

UNAIDS and WHO strongly advocate combination prevention as the most effective strategy to reduce HIV transmission. This includes correct and consistent use of male and female condoms, delaying sexual debut, having fewer partners, avoiding penetrative sex, male circumcision, reducing stigma and discrimination, and the removal of punitive laws. The male latex condom is the single, most efficient, available technology to reduce the sexual transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. The iPrEx study findings provide hope that men who have sex with men may have an additional means to protect themselves against HIV in addition to condoms.

UNAIDS and WHO will work with the study team and convene experts and key stakeholders to assess implications of these results for potential safe and effective delivery of PrEP as an additional HIV prevention tool for men who have sex with men. Close clinical evaluation, regular HIV testing, counselling to support pill-taking behaviour and safer sex, and safety monitoring are likely to be key components of effective PrEP programming.

The trial team at each study site will now provide access to the drug combination to all study participants, including those in the placebo group. This is in line with published good participatory practice guidelines and ethical standards for biomedical HIV prevention trials. UNAIDS and WHO welcome the efforts of the study teams to gather information on what implementation strategies for safe and appropriate PrEP work best.

Related

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

Status of HIV Programmes in Indonesia

24 February 2025

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

Lost and link: Indonesian initiative to find people living with HIV who stopped their treatment

Lost and link: Indonesian initiative to find people living with HIV who stopped their treatment

21 January 2025

Documents

Good participatory practice: Guidelines for biomedical HIV prevention trials (2011)

29 June 2011

The good participatory practice (GPP) guidelines provide trial funders, sponsors, and implementers with systematic guidance on how to effectively engage with stakeholders in the design and conduct of biomedical HIV prevention trials. In the GPP guidelines, “design and conduct of biomedical HIV prevention trials” refers to activities required for the development, planning, implementation, and conclusion of a trial, including dissemination of trial results.

Related

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

A shot at ending AIDS — How new long-acting medicines could revolutionize the HIV response

21 January 2025

To end AIDS, communities mobilize to engage men and boys

To end AIDS, communities mobilize to engage men and boys

04 December 2024

UNAIDS data 2024

02 December 2024

Documents

Ethical considerations in biomedical HIV prevention trials

01 July 2012

Well into the third decade of the HIV epidemic, there remains no effective HIV preventive vaccine, microbicide, product or drug to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition. As the numbers of those infected by HIV and dying from AIDS continue to increase, the need for such biomedical HIV preventive interventions becomes ever more urgent. Several such products are at various stages of development, including some currently in phase III efficacy trials. The successful development of effective HIV preventive interventions requires that many different candidates be studied simultaneously in different populations around the world.

Related

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

A shot at ending AIDS — How new long-acting medicines could revolutionize the HIV response

21 January 2025

Indicators and questions for monitoring progress on the 2021 Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS — Global AIDS Monitoring 2025

17 December 2024

Frequently Asked Questions — Global AIDS Monitoring 2025

17 December 2024

Documents

Speech by Michel Sidibé, Executive Director of UNAIDS, to the 2009 AIDS Vaccine Conference

19 October 2009

This is an exciting time to be among AIDS vaccine researchers—even more exciting than I anticipated when I accepted the invitation months ago.We have witnessed a significant moment in the AIDS field with the announcement of the results of the Phase III trial in Thailand of a combination HIV vaccine candidate. As you know, the results presented thus far from the Thai trial are modest. Yet that the results are not conclusive is to miss the point—the point is that they provide much needed hope to the scientific community.

Related

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

A shot at ending AIDS — How new long-acting medicines could revolutionize the HIV response

21 January 2025

55th meeting of the UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board

10 December 2024

To end AIDS, communities mobilize to engage men and boys

To end AIDS, communities mobilize to engage men and boys

04 December 2024

Related

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

Three Years On: From crisis to prospective recovery

20 February 2025

Impact of community-led and community-based HIV service delivery beyond HIV: case studies from eastern and southern Africa

30 January 2025

Related

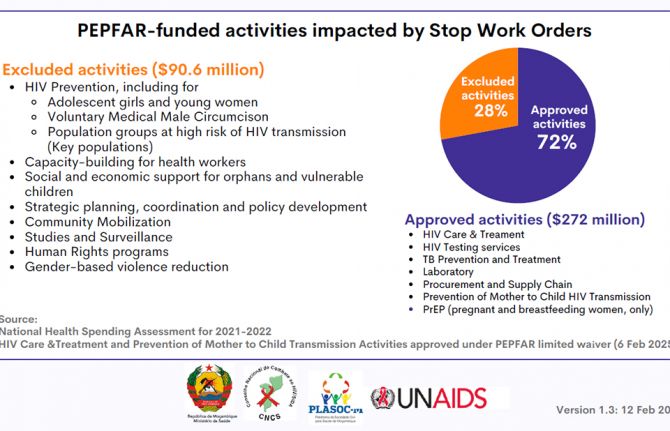

The impact of the United States foreign assistance pause on the community-led HIV response in Latin America

The impact of the United States foreign assistance pause on the community-led HIV response in Latin America

03 March 2025

Comprehensive Update on HIV Programmes in the Dominican Republic

Comprehensive Update on HIV Programmes in the Dominican Republic

19 February 2025

The critical impact of the PEPFAR funding freeze for HIV across Latin America and the Caribbean

The critical impact of the PEPFAR funding freeze for HIV across Latin America and the Caribbean

19 February 2025